Section 5: APS Values and promoting integrity

Integrity provides the licence for the public service to operate. This comes from values-based behaviour including the efficient and effective use of public resources.

The Hon John Lloyd PSM

presentation to the AHRI Professional Certification program

6 November 2015

Key points

- The effectiveness of the APS relies on a values-based culture that encourages trust and accountability.

- Internationally Australia is perceived to be one of the most corruption-free countries in the world.

- The level of serious misconduct in the APS remains low with fewer breaches of the APS Code of Conduct investigated in 2014–15 than in 2013&14.

- Most APS employees consistently agree their senior leaders, immediate supervisors and colleagues act in accordance with the APS Values.

- Agencies continue to develop their policies and procedures for managing integrity risks and dealing with reports of misconduct.

The legitimacy and effectiveness of the APS relies on a values-based culture that encourages trust and accountability. It requires employees to consider underlying principles when they make decisions and perform tasks. A robust culture of integrity and accountability requires that agencies have in place the processes, procedures and systems necessary to support ethical behaviour.

Integrity in the APS is broader than compliance with the legal framework and having low levels of corruption. It is employees and managers embracing a set of values that provides the public and the Government with confidence and trust in the way that advice and services are delivered.

Integrity toolkit

The Commission is working with the Attorney-General's Department and integrity agencies on developing a toolkit for managers to assist them to identify and manage risks to integrity. This toolkit will complement the Attorney-General's Department's publication, Managing the insider threat to your business: A personnel security handbook1 and the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity's online information on corruption prevention that includes a Corruption Prevention Toolkit and case studies.

Breaches of the APS Code of Conduct

The level of serious misconduct in the APS remains low with fewer breaches of the APS Code of Conduct investigated in 2014–15 than in the previous year. Agencies continue to instil a values-based culture by increasing ethical awareness and integrity through strong risk management and high levels of accountability.

The Act includes a statutory Code of Conduct setting out the standards expected of APS agency heads and employees. Section 15(3) of the Act requires agency heads to establish procedures for determining if an employee, or former employee, has breached the Code of Conduct and the sanctions that can be imposed if a breach is found. An agency head's procedures must have due regard to procedural fairness and comply with the basic procedural requirements in the Australian Public Service Commissioner's Directions 2013.

In June 2015, to assist agencies, the Commission launched a revised version of its guide Handling Misconduct: A human resource manager's guide. This guide is available on the Commission's website2

An important element of integrity in the APS is the reporting and investigation of allegations of misconduct by APS employees. In 2014–15, agencies reported finalising Code of Conduct investigations in relation to fewer employees 557 compared with 592 in the previous year. The proportion of investigations that found the Code of Conduct had been breached increased from 81% in 2013–14 to 84% in 2014–15. Failure to behave in accordance with the APS Values and Employment Principles and thus, to uphold the integrity and good reputation of the employee's agency and the APS, continued to be the most common alleged breach. This was a factor in 55% of finalised investigations in 2014–15 compared with 74% in 2013–14.

The most common sanction applied for a breach was a reprimand. The second most common sanction was a reduction in salary. The employment of 81 employees was terminated as a sanction for a breach of the Code of Conduct in 2014–15.

Perceptions of corruption in the APS

Internationally, Australia is perceived to have one of the most corruption-free public service systems in the world. The Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Australia eleventh among 175 countries and territories. This ranking is based on perceptions of aggregate corruption at every level of government—Commonwealth, state, territory and local.

In 2014–15, agencies advised that 100 of the 557 finalised Code of Conduct investigations involved corrupt behaviour. The types of corrupt behaviour included inappropriate use of flex time; misuse of personal leave to undertake paid employment; conflict of interest on selection panels; theft; and misuse of duties to gain a personal benefit.

The relatively minor nature of many of these reported matters may be inconsistent with what is understood in the community by the term 'corruption'. Nevertheless, misconduct of this kind still warrants appropriate attention and action.

Another indicator of corruption in the APS is employees' perception of its prevalence. Employees were asked if they had witnessed and reported perceived corruption in their workplace. For the purposes of the employee census, corruption in the APS was defined as:

The dishonest or biased exercise of a Commonwealth public official's functions. A distinguishing characteristic of corrupt behaviour is that it involves conduct that would usually justify serious penalties, such as termination of employment or criminal prosecution.

Results from the employee census show that 3.6% of APS employees reported they had witnessed another employee engaging in behaviour they considered serious enough to be viewed as corruption. Sixty-eight per cent of these employees reported they had witnessed cronyism, 24% reported they had witnessed nepotism and 23% reported they witnessed an APS employee acting, or failing to act, in the presence of undisclosed conflict of interest3. Of the employees who reported they had witnessed corruption in their workplaces, 34% reported the behaviour.

The definition of corruption, which was changed in this year's employee census, may have contributed to the increase in perceived corruption ―from 2.6% in 2013–14 to 3.6% in 2014–15. Similar to results from 2013–14, a large majority of employees witnessing corruption reported witnessing cronyism and nepotism.

Corruption in the APS is relatively low, however agencies are not complacent. They continue to develop and apply their policies and procedures for managing risks and dealing with reports of corruption or other forms of misconduct. In recent years, there has been an increased focus on integrity risks across all areas of agencies—from frontline contact points to agency support areas that may be susceptible to being compromised by criminal organisations.

Integrity and anti-corruption measures

The Commission is supporting the whole-of-government approach to integrity, including anti-corruption measures. Training in integrity and anti-corruption continues to be an element of the APS Leadership and Core Skills Strategy and associated learning programs. A continuing need exists for staff at all levels to understand the ethical frameworks that guide behaviour and decision-making in the APS.

This complements the work of other APS agencies to improve the integrity framework. For example, the Attorney-General's Department has developed the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework which sets out the key requirements of fraud control. Additionally, the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity has released its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan that provides a systematic approach to assessing and controlling integrity risk. The Department of Finance has developed guidance on proper management of Commonwealth resources, including the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework.

Ethical leadership

Results from the APS employee census indicate that leaders play a critical role in establishing the ethical climate or culture in the workplace. This, in turn, contributes to managing issues such as employee perceptions of workplace corruption.

A measure of ethical leadership is how consistently leaders at all levels behave in accordance with the values of the APS. The impact of this on organisational behaviours can be seen in the relationship between ethical leadership and employees' perceptions of how their agencies deal with corruption. Results from the employee census show a strong positive relationship between the two. Employees who believe their senior leaders act in accordance with the APS Values also believe their agency deals with corruption well. The relationship can be seen when examining employee perceptions of their senior leaders' ethical behaviour.

Figure 3: The relationship between ethical leadership and perceptions of how well agencies deal with corruption

Source: Employee census

The impact of ethical leadership is not limited to perceptions of how well the agency deals with corruption. Research on the risks of psychological injury in the workplace has shown a link between workplace corruption and mental health.4 Data from the employee census shows similar findings.

Analysis of results from the employee census suggests ethical leadership, particularly at the senior levels, influences workplace practices related to employee psychological health which in turn effects the risk of both depression and job strain. When employees perceive that their senior leaders always act in accordance with APS Values, they also view their workplace as having the practices in place to reduce the risk of psychological injury.

APS Values

Results from the employee census demonstrate that most APS employees consistently agree that their senior leaders, immediate supervisors and colleagues act in accordance with the APS Values. In 2015, however, there was a drop in the proportion of employees who agreed that their senior leaders 'always' or 'often' act in accordance with the Values ―69% this year compared to 74% in 2014.

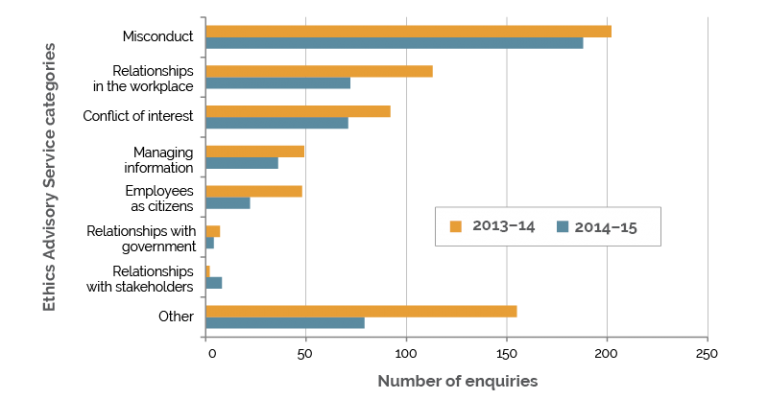

Ethics Advisory Service

The Commission continues to support agencies to promote the APS Values and Code of Conduct within their organisations. The Ethics Advisory Service provides advice to managers and employees on ethical issues and the Commission supports Ethics Contact Officers in agencies and delivers training across the APS. Embedding the values in agency systems, processes and procedures, as well as individual behaviour, continues to strengthen ethical decision-making and integrity.

During 2014–15, 565 employees from 77 agencies contacted the Ethics Advisory Service for advice. Forty-three per cent of enquiries came from individual APS employees and 38% came from corporate areas; some callers chose to remain anonymous. Of those enquirers who gave a classification, 28% were APS 1–6 staff, 37% were EL 1 level, 28% were EL 2 level and 6% were SES levels.

The nature of enquiries in 2014–15 remained consistent with the previous year.

The highest proportion of enquiries again related to the management of misconduct in agencies.

Figure 4: Enquiries to the EAS by category, 2013–14 and 2014–15

Source: Ethics Advisory Service

Bullying and harassment

Workplace bullying continues to be a concern in the APS. The APS Code of Conduct requires employees to treat everyone with respect and courtesy and without harassment when acting in connection with their employment. Senior leaders are expected to promote the Code of Conduct by personal example or other appropriate means.

Data from the employee census demonstrates that over the past decade, between 15% and 18% of employees reported they were bullied or harassed in the workplace. Bullying could be by a client, a colleague or a manager. This year, 17% of employees reported they had been bullied or harassed in the twelve months prior to the employee census. Perceptions of bullying and harassment in the workplace have remained relatively stable across time, between 15% and 18%, which corresponds with the 2014 result.

Indigenous employees and employees with disability were more likely to report they had been bullied or harassed than other APS employees. These employees were also more likely to report the behaviour than other APS employees.

Bullying and harassment is often influenced by perspectives, and what is perceived as harassment by one person may be, for example, proper management action to another. Reasonable administrative action, undertaken in a reasonable way, does not constitute harassment regardless of how it may be perceived.

Harassment remains a real concern, nonetheless, and is often investigated as a suspected breach of the Code of Conduct when reported. The subjective experience of harassment may provide an explanation for the relatively low proportion of Code of Conduct investigations that lead to a finding that harassment has occurred.

Not all allegations of misconduct need result in Code of Conduct action. Other means of addressing bullying and harassment can include alternative dispute resolution or performance management action.

As of 1 January 2014, APS employees who reasonably believe that they have been bullied at work can apply to the Fair Work Commission for an order to stop the bullying. To date, there have been no orders issued relating to employment in the APS.

1 Attorney-General's Department 2015, Managing the insider threat to your business: A personnel security handbook, version 2.1, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, viewed 2 November 2015.

2 Australian Public Service Commission 2015, Handling Misconduct (2nd edn), Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, viewed 2 October 2015, <http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/hand…;.

3 Percentages do not add to 100% as respondents could report having witnessed more than one behaviour.

4 Dollard, M 2012, Workplace psychosocial risks to mental health: National surveillance and the Australian Workplace Barometer project. Presentation to Mental Health in the Workplace Workshop, Menzies Research Centre, Tasmania.