Chapter 1: Commissioner’s overview

Reform has been a key focus for the APS this year. The Government continues its endeavours to create a more productive, efficient and effective public service. In May 2018, the Government announced two approaches to further reform the APS.

The first approach is an ongoing Roadmap for Reform (the Roadmap) to be implemented by Secretaries.1 The Roadmap focuses on short to medium-term strategies in six streams designed to improve:

- Citizen and business engagement—ensuring more effective engagement between the public sector, citizens, business, and innovators when designing and delivering policies, programs and services.

- Investment and resourcing—better aligning funding to deliver government priorities and meet service delivery expectations.

- Policy, data and innovation—making the best use of data to support policy development and decision making and improve innovation.

- Structures and operating models—ensuring APS operating models support integration, efficiency and a focus on citizen services.

- Workforce and culture—adopting workforce practices that will meet future needs, including through strengthening talent management, data analytical capability and digital skills.

- Productivity—developing the best contemporary measures for public sector productivity and using this to improve administration.

The second approach is an Independent Review of the APS to ensure the APS is fit-for-purpose for the coming decades. The Review is being conducted by a six-person panel. The panel is chaired by Mr David Thodey AO, and includes Ms Maile Carnegie, Professor Glynn Davis AC, Dr Gordon de Brouwer PSM, Ms Belinda Hutchinson AM, and Ms Alison Watkins.

The panel is due to report to Government by mid-2019.

The pressure for reform#

Current APS reform work is in response to the need to maintain a strong and effective public service in the face of increasing challenges.

Like many other institutions in Western democracies, the APS is under pressure. The public has high expectations about how complex policy problems are solved and how services are delivered.

The acceleration of technology, the speed of decision making, global interconnectedness and changes brought by social media, have profoundly altered Australian society, and the expectations Australians have of government institutions.

Evidence also exists of declining trust in government institutions. There are many global measures of trust in government, however one of the most long-standing is the Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual online survey of trust in 28 markets around the world. In 2018, results showed an ongoing decline in the trust Australians have across all three tiers of government.

The APS relies on social licence and trust from the public. Data is fundamental in responding to public expectations that policy and service delivery be personalised and tailored to local community needs. Appropriate safeguards and community consultation are needed when implementing data and digital services, to avoid undermining the broader agenda of effective policy implementation. The declining trust in institutions could also lead to increased scrutiny and calls for greater transparency and accountability, including of the APS. It is therefore as important as ever that the APS maintains strong integrity foundations.

The APS is not broken, but it does need to be ready to respond quickly to government and changing community needs and to take advantage of emerging technologies. While accelerated change is needed, this must be managed carefully. The Government and the public want a sense of continuity and stability from the APS. Services and functions still need to be delivered and sound advice provided.

Current state of play#

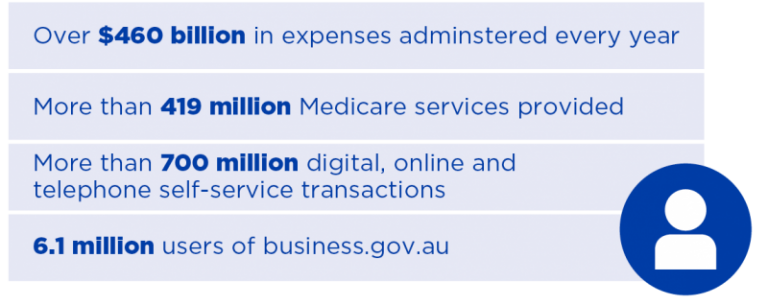

A high-performing APS is critical to the effective delivery of government services to the Australian community (Figure 2). Some 150,000 employees working across Australia and overseas through 18 departments and more than 100 agencies and authorities deliver a wide array of services.

Figure 2: Delivering for citizens and businesses

For many years, Australia has performed strongly on international comparisons of public sectors. In 2017, Australia ranked 3rd overall in the International Civil Service Effectiveness Index.2 A closer look at the measures shows that Australia strongly performed in regulation, crisis/risk management, inclusiveness and digital services. Australia fell outside the top five in other areas, such as policy making and human resource (HR) management.

The 2017 Government at a Glance data, produced by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), also shows that Australia performs well in a number of areas, including integrity, regulation openness of government and managing national crises.

The APS no longer has the monopoly it once had. As an enduring institution, the APS still has authority, but it is working in a much more contested environment. The advice from the APS needs to be well-argued, persuasive and open to challenge by political advisers, think-tanks, lobby groups and non-government organisations (NGOs). This is the reality, and the APS must be able to deliver in this environment.

Civil society, the private sector and single-issue groups are highly mobile, well-funded and adept at using social media to influence reform. The APS has a responsibility to bring a wide lens to any issue and ensure that the Government has all the relevant data and analysis it needs to make decisions.

There has been a shift in the very nature of power. Because of new communication technologies, influence has flowed to coalitions and networks. This means the APS has to engage more actively with civil society and the private sector to ensure its positions are well understood and to provide sound advice to government.

The APS has to think imaginatively about its working relationships with ministers and their offices. An effective APS requires that it be accepted that talented employees need to have the opportunity to work in ministerial offices to give them a deeper understanding of the speed with which matters move, and the pressures that quickly bear down on ministers. Understanding these pressures makes for better public service advisers.

Similarly, it is incumbent on the APS to assist political staffers to understand how to use and work with the public service. It is imperative that the APS remains impartial and apolitical. However, the APS also needs to be politically astute. Government works at its best when ministers, their offices and the public service work together in pursuit of an outcome.

Fragmentation and silos remain across the APS and all levels of Australian governments.

We cannot fix complex problems through stove-piped processes. The taskforce model for policy development and implementation is likely to emerge as a model for the future. The ability to quickly configure around an issue is going to be crucial in managing complexity. Accountability and resourcing needs to be shared.

The community does not differentiate between different levels and areas of the public sector. To meet increasing community expectations, the APS must work more closely with colleagues across the APS, as well as with colleagues in state and territory public sectors, and with local government and their communities.

David Thodey AO has recently spoken about early themes emerging from the Independent Review of the APS. These include the need to:

- have a clear statement on and agreement of the purpose, culture and behaviours of the APS across all stakeholders

- value and respect the institution of the APS and the people who work in it—the public service profession

- understand the changing nature of leadership and functional expertise required in the APS

- invest sufficient time and resources to continually develop the APS workforce and maintain core capability, while developing the skills and capabilities for the future

- understand that the nature of an impactful and effective APS is driven by outcomes and cross-government collaboration

- ensure the APS is both innovative and responsive in meeting the evolving expectations of the community and government

- understand the needs of the public and achieving a modern citizen-centric public service

- ensure contemporary governance, management processes and organisational design.

These themes are well-articulated and the Independent Review is likely to be a highly influential document. That said, the APS does not need to wait for the outcomes of the Review to work on improving its performance. There is much more we can do now.

The Government’s program for modernising the APS has been underway for some time.

The APS Reform Committee of the Secretaries Board is leading work to reform the APS, including improvements to delivering corporate services through the shared services program and developing a whole-of-government citizen and business engagement strategy, with linkages to a digital strategy to improve government service delivery. The ARC is also overseeing work to improve policy and innovation capability across the APS.

A set of projects are in train to transform the use of government data. This includes work through the Data Integration Partnership for Australia to support more comprehensive data analysis and improve policy development and program implementation.

A data literacy program was designed in partnership between the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and released in 2018. The program included a ‘Using statistics’ workshop, which was piloted twice in mid-2018 before general release.

The APSC is also working in partnership with the Digital Transformation Agency to support the Government’s digital transformation agenda through programs to increase digital capability in the APS.

In 2017–18, a pilot program for senior executives concentrating on digital leadership was introduced. The Leading Digital Transformation program is designed to increase the confidence and capability of senior executives to lead digital programs and change.

An APS workforce for the future#

The role of the APSC is central in building and maintaining the capability of the APS. Section 41 of the Public Service Act, in its simplest terms, requires the Australian Public Service Commissioner to work with the APS to ensure its professionalism, integrity and effectiveness.

Under the Roadmap announced in this year’s Budget, the APSC is tasked with developing a ‘whole-of-government workforce strategy to drive modern workforce practices, inform future capability requirements and help prepare the public sector employees for the future.’

The capability of the APS workforce and the ability of the APS to mobilise this capability is vital to the success of a public sector fit for the future.

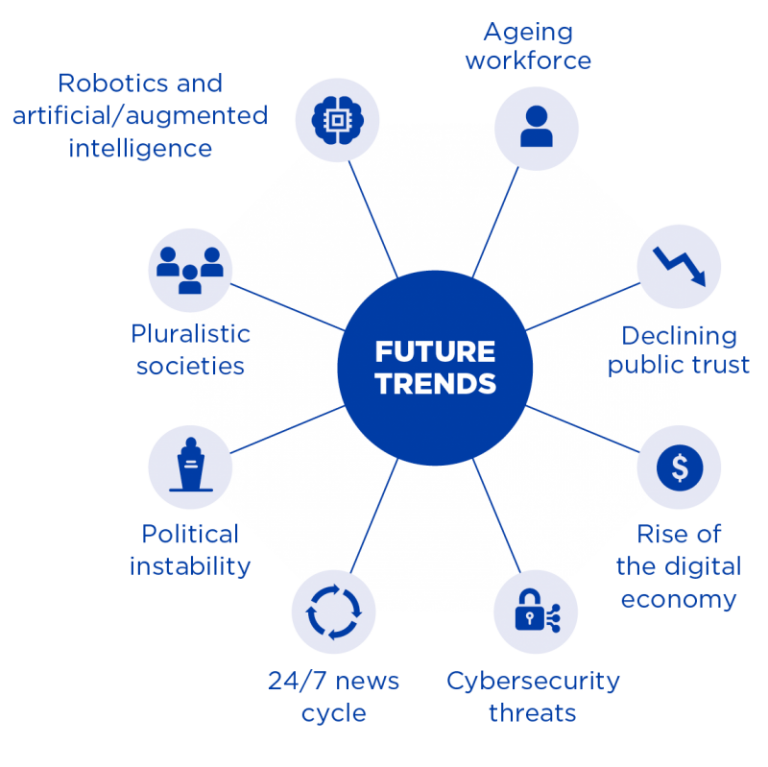

A number of global and local trends have implications for the future of the APS workforce (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Global and local trends with implications for the future of the APS

The APS-wide workforce strategy will be built on three core components to ensure the APS has the:

- culture, values and behaviours required to support a modern, professional workforce

- capabilities required for the future

- leadership required to steward the APS through change.

Underpinning the strategy will be a range of initiatives to:

- attract people with the right skills, experience and mindset, mobilising them when and where needed. These people may be from within the APS or from the private sector, not-for-profit sector or other jurisdictions. They may also be consultants or contractors.

- identify and develop the evolving capabilities needed in the APS workforce to deliver government outcomes.

- create a flexible and adaptive environment to meet the needs of citizens, the workforce and government.

The high-level themes of this year’s report focus on these three components—culture, capability and leadership.

Culture#

Culture is the foundational set of values and behaviours that underpin the APS. A culture that reflects a professional public service, has a strong focus on integrity and the principles of good administration is central to the democratic process and the confidence the public has in the public service.

The APS is well regarded by international benchmarks and peers for its integrity processes and structures. There can, however, be no complacency. It is difficult to build trust and easy to lose it.

With a more mobile workforce moving in and out of the public service, the focus on integrity needs to remain strong.

With changing expectations of the APS and the changing nature of work, the APS will need to assess if the current set of values and behavioural expectations remains relevant and resonates with a modern APS.

Inclusiveness remains a crucial cultural value. The APS needs to reflect the diversity of the Australian community.

It is pleasing that this year the APS achieved equal gender balance at secretary level. However, the diversity of the APS trails that of the broader Australian community, particularly at the SES levels. We need to increase our efforts. The APS needs a wider view to ensure it does not become inward looking and insular.

A strong change management culture is needed if the APS is to effectively address future challenges.

When considering change management in their agencies, just over one-third of respondents to the 2018 APS employee census agree that change is managed well. When considering the role of the SES in managing change, 58 per cent agree that they effectively lead and manage change. There has only been a slight increase to these results in the past five years.

In 2015 and 2017, the APSC asked agencies to self-assess their change management capability. Eighty-seven per cent assessed they needed to increase this capability. Forty-six per cent reported their change management capability had declined since 2015.

The development of a positive risk culture is also needed to support greater levels of innovation. A strong risk averse culture prevents the APS from being open to new ways of responding to government and citizen demands and making the most of opportunities, including emerging technologies.

The APS has a history of being risk averse. In the State of the Service Report 2013–14, Stephen Sedgwick AO reported that external and self-assessments of APS practice suggested that ‘risk management is seen as a compliance exercise rather than a way of working.3

Five years later, the recent Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (Cwlth) (PGPA Act) review continues to raise concerns about the level of risk management maturity reporting that:

… risk practice across the Commonwealth is still relatively immature. There is still significant work to be done to embed an active engagement with risk into policy development processes and program management practice, and to have officials at all levels appreciate their role to identify and manage risk.4

The 2018 APS employee census asked questions about employee perceptions of risk management and risk culture within their agency.

Most respondents agreed that their agency supports escalating risk-related issues to managers. Almost two-thirds of respondents agreed that risk management concerns are discussed openly and honestly. However, only 28 per cent of respondents agreed that appropriate risk taking is rewarded in their agency. A large proportion of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the questions posed.

These results suggest that a significant cohort of employees may not understand their agency’s risk management framework, may not observe or experience risk management in action, or simply do not know how the statements apply in practice in their agency. This suggests there is some way to go in building an appropriate risk culture in the APS.

Capability#

Like organisations worldwide, building capability for the future is an APS priority. The nature of work is changing with rapid advances in computer power and data growth, advances in artificial intelligence, digitalisation and automation. An ageing workforce and younger generations entering the workforce are changing the way people want to work. Increasing importance is placed on soft skills, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) skills and lifelong learning.

At the same time, the APS will continue to require professional public service capabilities, such as policy expertise, to deliver to the standards government and citizens expect.

The APS also needs to mobilise capabilities when and where needed. The traditional view of mobility has been focused on the individual moving between departments or portfolios. This equates to about 2.5 per cent of employees per year.

The APS has not sufficiently focused on mobility both between agencies and in and out of the APS. Mobility can foster diversity of thinking, contestability of ideas and assist in capability development. Increased mobility will lift the overall capability of the APS, not just the individual.

The workforce of the future will be more mobile. People will have multiple careers and will engage in more gig or short-term work.

The APS needs to be flexible to respond quickly to emerging issues and to use our workforce appropriately in response. However, balance is needed. Too much, or poorly targeted, mobility can have the adverse impact with the APS losing subject-matter expertise.

Deep expertise is and will remain crucial to APS performance. This is particularly the case in specialised agencies, often sitting outside of departments, including those with specialised regulatory functions.

Experience outside of the APS is also critical in building capability. There is a need for more porous boundaries in and out of the public sector and stronger connections with the private sector, not-for-profit sector, academia, and state and territory jurisdictions.

In his recent address5 to the APS, the Minister for Finance and the Public Service asked the APSC to consider ways to rotate public servants through state and territory governments, private sector companies and the third sector. Such a program offers a way to build understanding and familiarity across these sectors and improve APS capacity.

Leadership#

Strong and effective leadership is essential to successful reform. In 2017, the Secretaries Board endorsed a set of leadership capabilities for senior leaders. These provide guidance for the SES in their important leadership role of the APS as it adapts to best support government and citizens.

In the 2018 APS employee census, employees rated their supervisors favourably on all questions.

Most APS employees also viewed their SES managers positively, although less so than perceptions of immediate supervisors. APS employees were mostly likely to agree that their SES manager was of high quality at 65 per cent, an increase from 62 per cent in 2017.

The lowest result was in response to whether SES gave time to identify and develop talented people, at 45 per cent. This is a small increase on last year’s result of 43 per cent.

Consistent with past years, APS employees rated SES across their organisation less favourably than their immediate SES and supervisor. In particular, employees are less likely to agree that their SES work as a team (only 43 per cent of respondents agree). This needs to be a focus area for improvement.

Data from the 2018 APS agency survey indicates that one of the priority areas for capability development across the APS is leadership and management. Specific leadership development areas include resilience and change management. Leadership development for APS 5 and 6, and Executive Level (EL) employees is a priority for some small agencies.

Agencies suggest a number of factors are driving this demand, including the need to operate effectively in an environment of continuous change, complexity and uncertainty.

1 Department of Finance (2018), Budget 2018–19: Agency Resourcing Budget paper No. 4, Canberra.

2 International Civil Service Effectiveness (InCiSE) Index, 2017 - external site, PDF (accessed 13 September 2021).

3 State of the Service Report 2013–14, p. 11.

4 Alexander, E and Thodey, D (2018), Independent Review into the Operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule, p. 20.

5 https://www.financeminister.gov.au/speech/2018/10/10/address-australian… - external site (accessed 16 October 2018).