Strengthen employment outcomes

"To be fit for purpose for the coming decades, the APS must ensure a diverse and inclusive environment that accepts individuals’ differences, embraces their strengths and provides opportunities for all employees to achieve their potential."- Our Public Service, Our Future. Independent Review of the Australian Public Service

Diversity and inclusion initiatives play an important role in strengthening employment outcomes across the APS. Diversity and inclusion is a powerful enabler of performance, and APS agencies that leverage diversity and inclusion will be better positioned to adapt to future challenges and increase productivity. Improving employment outcomes for employees from diversity groups will play an important role in shaping a more diverse and inclusive APS. This will set us apart from other sectors as an employer of choice, significantly strengthening the APS employee value proposition and contribute to building a world-class public service into the future.

Career pathways

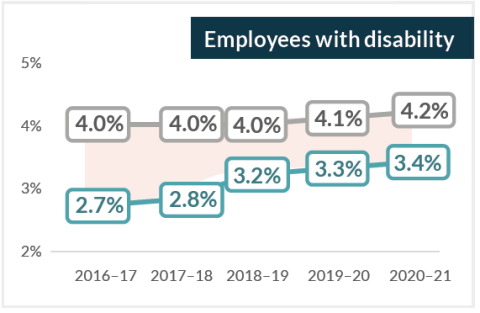

Internal promotions are an important career pathway in the APS. There has been a general upwards trend in the proportion of promotions of employees in diversity groups over the past five years.

Difference between proportion of all promotions and proportion of overall workforce by financial year

|

Women were over-represented in 2018-19 and 2019-20, but returned to equivalence in 2020-21. |

|

Promotion of First Nations employees is generally in line with their workforce representation, but dipped in 2018-19 and spiked in 2019-20. |

|

Employees with disability are consistently under-represented, although the gap has narrowed since 2016-17. |

Promotions to level of employees from diversity groups compared with overall promotions in the 2020–21 financial year.

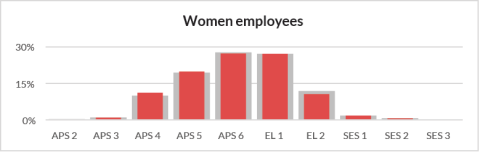

The "level to" of promotions of women is consistent with those of all APS employees.

The "level to" of promotions of employees with disability is generally consistent with overall promotions, but they were slightly under-represented at more senior levels.

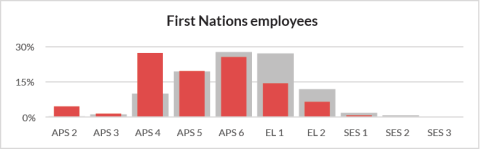

The "level to" of promotions of First Nations employees is not consistent with overall promotions. First Nations employees promotions are higher at lower levels and significantly under-represented at EL1 and above.

84% of all First Nations employees are employed at APS classification levels compared to 70% of the overall workforce. When promotion opportunities occur, there are simply not as many First Nations staff at higher levels to compete for these higher level positions. Additionally, many First Nations employees work in regional or remote locations where higher classification roles are not available; or in job families and roles with limited career pathways to senior positions. Unless priority or focused action is taken for career progression and recruiting First Nations people into leadership positions, it will be difficult for agencies to increase representation at senior levels.

|

The retention and development of First Nations employees will be a critical part of developing the talent pipeline for senior levels. |

|

Identify opportunities to better support First Nations employees to progress to higher levels. This could be done through dedicated mentoring programs, development of career pathways, or targeted leadership training opportunities. Consider opportunities to partner with other agencies. |

|

Improving the cultural capability of supervisors and recruitment panels and assessors will help to ensure equitable outcomes in recruitment processes. |

Access to learning and development

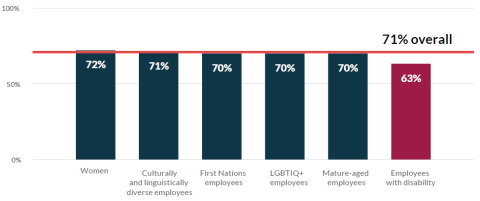

When asked about their access to learning and development, most employees (71%) agreed they have access to formal and informal learning and development opportunities. This was consistent across most diversity areas, however, employees with disability were less likely to say they had access.

|

Supporting employees to access learning and development opportunities is a way for agencies to engage their workforce, increase employee knowledge and improve retention rates. |

|

Ensure employees with disability have access to learning and development opportunities by making the activities accessible. For example, consider whether online courses can be read by an e-reader, or how accessible venues are for people with different mobility considerations. |

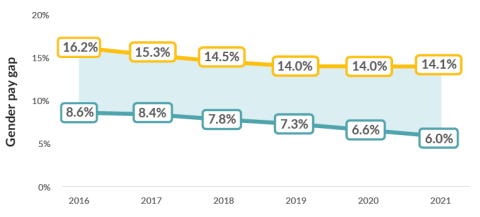

Gender pay gap

The average gender pay gap in the APS has continued to trend down over the last six years, which is likely to have been driven by the increasing representation of women at higher classification levels[i].

In 2021, the APS average gender pay gap was 6.0%. The APS has one of the lowest gender pay gaps in Australia, significantly lower than the national gender pay gap of 14.1% in 2021 reported by the Australian Workplace Gender Equality Agency[ii].

Over the last five years, the APS gender pay gap has consistently been around 7 percentage points lower than the national gender pay gap, in 2021, this gap between the APS and national level increased to 8.1%.

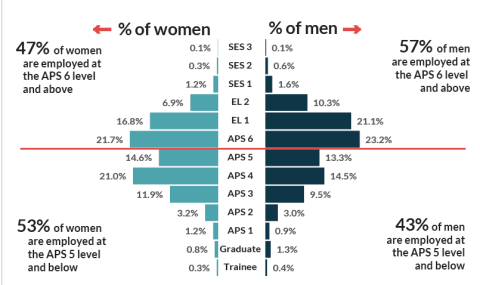

The majority of women employed in the APS are employed at the APS 5 classification or below; while the majority of men are employed at the APS 6 level and above. The gender pay gap calculation methodology takes into account the difference in part-time and full-time work. Overall, the representational differences between the classification levels are not significant and may only have a small influence on the gender pay gap.

Classification and distribution of employees by gender:

|

Prioritise increased representation of women at senior leadership levels and explore greater gender diversity in specific occupations and job families. |

Workforce planning

Diversity and inclusion should be a focus area for an agency’s workforce plan considering it is a key step to help agencies to more effectively drive workforce transformation and improve business outcomes. Workforce planning is an essential mechanism to manage the increasingly multifaceted and complex business of public administration in an uncertain world, by ensuring the workforce needed to deliver is being considered and actively planned for by public sector entities.

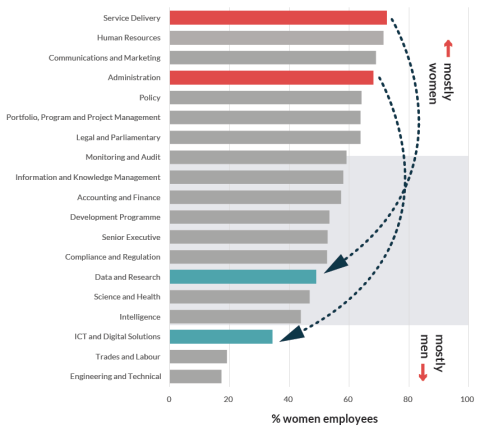

Strategic workforce planning can help agencies identify and address issues that will disproportionately affect employees from diversity groups. The APS Centre of Excellence for Workforce Planning predicts that, over the next 10-15 years, automation will decrease the number of administration and service delivery roles required in the APS. This will have a disproportionate impact on women, First Nations employees, and employees with disability, who are over-represented in these job families.

Strategic workforce planning is required to create transition pathways to support employee in occupations that will be most impacted by automation to reskill and transition into roles in high-growth occupations with skills shortages.

|

A strategic workforce planning approach will be required to transition APS staff working in roles projected to decline into other high demand areas. |

In 2021 the APS Centre of Excellence for Workforce Planning conducted a review of agency workforce plans collected through the annual agency survey. 28 workforce plans were submitted (spanning 2016 to 2023+) and analysed to identify the extent to which agencies recognise and reference diversity and inclusion when managing their workforce.

89% of the submitted workforce plans identified implementation of diversity and inclusion actions. The diversity cohorts considered in the plans were:

12 First Nations |

10 Disability |

8 Culturally and |

8 Gender |

5 LGBTQIA+ |

Parental Entitlements |

|

Drive purposeful and systemic change by improving the integration of diversity and inclusion principles and processes into all APS workforce plans, business plans and workforce policy. |

Case study – Job Sharing Susan Fitzgerald and Megan Leahy, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C)

Our SES Band 1 job share arrangement has offered us significant flexibility and an ability to (mostly) ‘switch off’ on our non-work days.

In late 2020, when we were each returning to work from extended maternity and carers leave, we presented a job-sharing proposal to our senior SES. While the arrangement came about organically and was initiated by us, it was whole-heartedly supported by PM&C, where the Flexible Work Policy has a starting position of ‘how can we make this work?’ on many different kinds of flexible work arrangements. Our direct bosses, in particular, have really gone in to bat for us. The combination of corporate and local support has been invaluable.

Key to our day to day success has been putting the right systems in place, flexibility, and good communication.

Early on, we met with a coach to establish processes and unpack our personal motivations and work styles. We do a strong handover, know which decisions we need to consult each other on, and have regular review points.

Our working styles are different, but complementary – staff have commented on how the different perspectives and experiences we both bring to the role means we approach an issue from all sides and augment one another’s contributions. Having a very similar work ethic has been so important to building mutual trust and ensuring the experience is seamless for our stakeholders and staff.

We put a lot of effort into outwards communication, so our Branch, colleagues and Band 2 know who to go to on what days. Our Executive and the Prime Minister’s Office can contact either of us on any day and know their requests will be actioned.

The greatest challenge is the time it takes to catch up on the days we’re not in the office and to do handover. We each work 3 days a week, with an overlap day. Because of the reactive and fast moving nature of PM&C, we do the same job on different days, rather than each of us leading separate pieces of work. This means we are both across much more than 3 days a week worth of content.

Our job share has meant we can spend more uninterrupted time with our families without losing momentum in our careers. And PM&C gets 2 sets of skills, experience and perspectives in one role, which we think is a pretty good deal!

[i] Commonwealth of Australia, 2021 Australian Public Service Remuneration Report 2020. Found online. p.24