2.3 Gender equality

The APS continues to lead the way in many aspects of gender equality. Female representation is strong, with the APS now comprising 60.4% women. For the first time, the APS has achieved gender balance at most senior leadership levels, and the gender pay gap continues to decline.

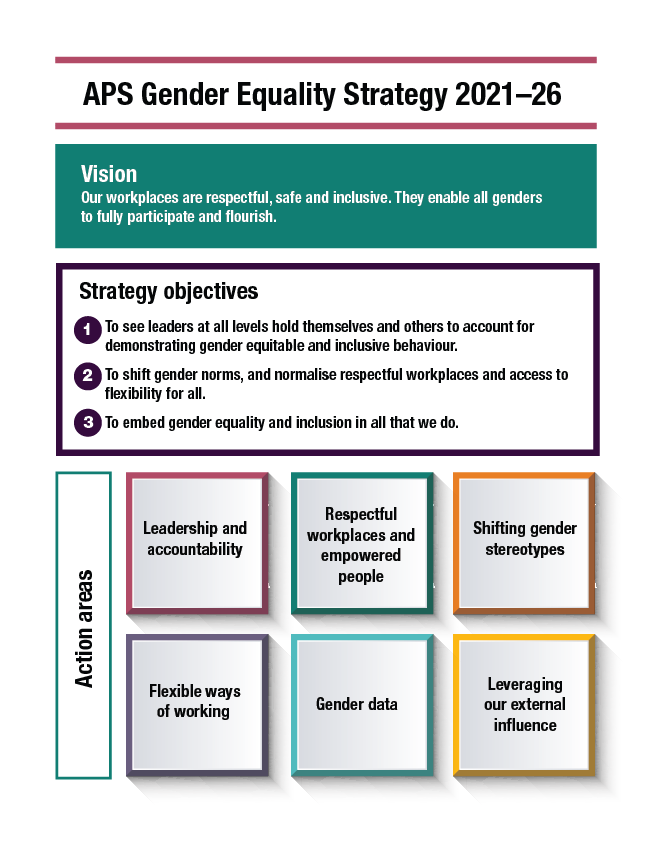

Despite this progress, gender equality remains a focus and there is still much to do. The APS needs to embed areas of strength and identify and respond to opportunities to further gender equality. To support this the APS Gender Equality Strategy 2021–26 was launched in December 2021.

This is not just a ‘women’s strategy’. It is a strategy that prioritises leadership and role modelling, greater gender diversity in specific occupations, safe and respectful workplaces, and continued focus on the gender pay gap (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7: Summary of the APS Gender Equality Strategy 2021–26

Source: APS Gender Equality Strategy 2021–26

Women in leadership

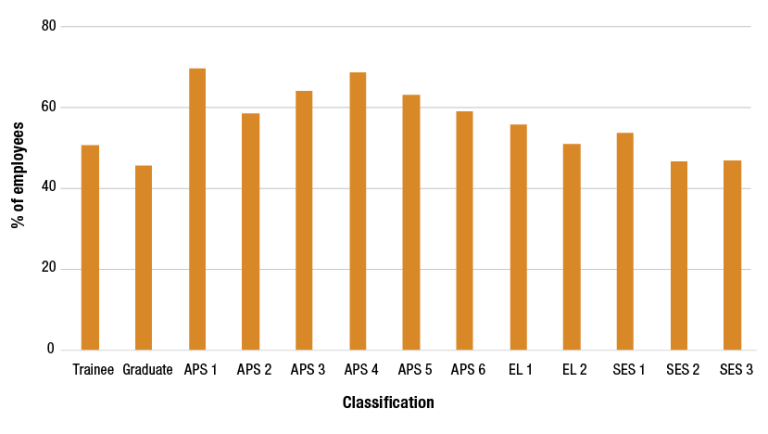

The proportion of women in leadership positions continues to grow, with women making up 52% of the SES. The greater proportion of women at lower classification levels (Figure 2.8) continues, but the APS expects a positive flow-on effect from the increasing number of women in leadership roles. Change happens when leaders lead by example and employees can see themselves in the leadership cohort. With targeted development programs and communication, women in the APS 4 to APS 5 levels are expected to feed into leadership levels.

Figure 2.8: Proportion of women in each classification (30 June 2022)

Source: APSED

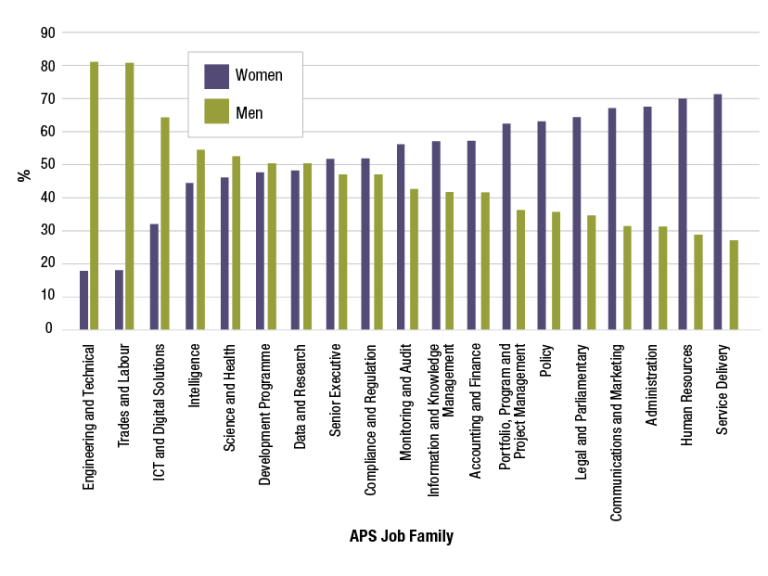

While the number of women in leadership roles continues to grow, a high proportion of women fill roles at lower classification levels doing work more likely to be automated as technology evolves. With high proportions of women in the areas of service delivery, HR and administration (Figure 2.9), these impacts present an opportunity for reskilling and transitioning to different, higher-paying roles15 in in-demand or emerging occupations. Over time, these targeted reskilling efforts are expected to change the shape of Australia’s workforce, by increasing the proportion of women in traditionally male-dominated fields including information and communications technology (ICT) and project management.

Figure 2.9: Proportion of APS Job Family by gender (30 June 2022)

Note: A Job Family represents functionally similar jobs that perform related tasks and require similar or related

skills and knowledge.

Source: APSED.

Programs to build leadership capability for women are already underway in areas of work that hold a high proportion of women at lower classification levels. Initiatives such as Coaching for Women in Digital and Women in IT Executive Mentoring are examples of approaches seeking to prepare women for the future.

| Bridging the gender gap in digital roles | ||

|---|---|---|

(Image: nenetus/Adobe Stock)

The Digital Profession is helping to create a more diversified and digital-ready APS workforce through programs and initiatives targeting groups historically under-represented in digital roles. |

||

| Two programs, Coaching for Women in Digital and Women in IT Executive Mentoring, aim to develop leadership skills, increase the number of women in leadership roles and reduce barriers to women’s career progression. This is vital to help foster a culture of innovation and the change needed to support digital transformation in government. | ||

| The 1,000 APS digital traineeships announced at the Government’s Jobs and Skills Summit (September 2022) will also provide opportunities for women, First Nations peoples, older Australians, and veterans transitioning to civilian life. By providing flexible training alongside employment, the APS Digital Traineeship Program will unlock opportunities for people, including women, wanting to reskill so they can more fully participate in the workforce. | ||

| These programs, and other Digital Profession initiatives, are helping to build the digital capability and diversity the APS needs to support digital transformation and continue to deliver quality outcomes for the people and businesses of Australia. | ||

| 'The program really does try to get you to be self-reflective in a positive but realistic way. The focus on strengths was a revelation for me. It has allowed me to share my knowledge, enthusiasm for learning and support my team more confidently.'

- Helen – participant, Coaching for Women in Digital program, 5 August 2021. |

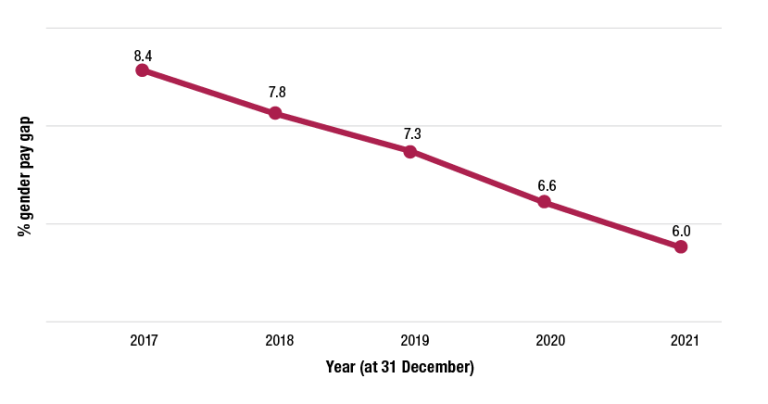

APS gender pay gap

The gender pay gap across the APS in 2021 was 6.0%, a decrease from 6.6% in 2020 and a continuation of a steady downwards trend since it was first reported in 2015. In 2021, the APS gender pay gap was less than half the national gender pay gap of 14.1% (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10: Average gender pay gap trends (2017 to 2021)

Source: APS Remuneration Report

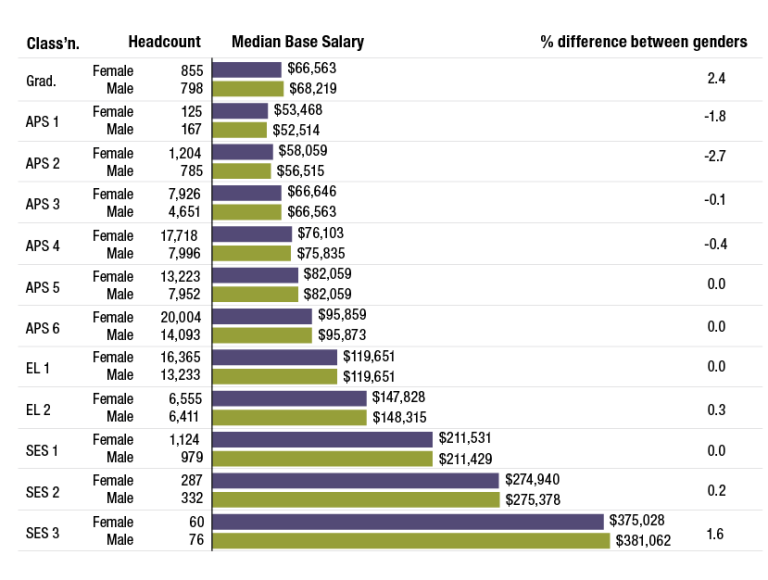

The APS gender pay gap calculation is based on the methodology used by the ABS and the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) and uses average base salary to allow for comparisons across sectors. Another method to measure gender equality in the APS is the difference in median base salaries at each classification level. As shown in Figure 2.11, the greatest difference in median base salary in 2021 occurred at the APS 2 level, 2.7% in favour of women. Four classifications had an observable difference in median base salaries in favour of men: Graduate, EL 2, SES Band 2 and SES Band 3 levels. Four classifications at the APS 1 through APS 4 levels had an observable difference in base salaries in favour of women. All other classifications had negligible differences.

Figure 2.11: Median base salary by gender and classification (31 December 2021)

Note: The percentage difference between genders is the difference between male and female median base salaries expressed as a percentage of male earnings.

Source: 2021 APS Remuneration Report

The factors influencing and contributing to the APS gender pay gap are complex and varied. They include:

- higher representation of women at lower classifications

- the impact on career progression for women accessing maternity leave or caring arrangements

- the differences in negotiated conditions and remuneration across APS agency enterprise agreements and policies.

Solving the gender pay gap in the APS is complex and is linked to the need for broader societal change to remove barriers to women’s workforce participation, along with fair and equal pay. The APS-wide work in implementing the Gender Equality Strategy and APSC’s work in reviewing the Maternity Leave (Commonwealth Employees) Act 1973 are both designed to help drive the gender pay gap down to inconsequential levels.

Review of the Maternity Leave (Commonwealth Employees) Act, 1973

The review of the Maternity Leave Act began in November 2021. It is the first comprehensive examination of parental leave entitlements in the APS for more than 40 years.

The review aims to ensure the APS remains an employer of choice in providing appropriate support to new parents, promoting gender equality and inclusion, and providing increased flexibility. It is exploring:

- eligibility and entitlements

- health needs of birth mothers

- superannuation on parental leave and

- creating a more equitable landscape for non-birth parents.

The review is also drawing comparisons with state public service offerings and private sector employers to deliver a suite of recommendations intended to bring the APS in line with community expectations and what is expected as a model employer.

Shifting gender stereotypes

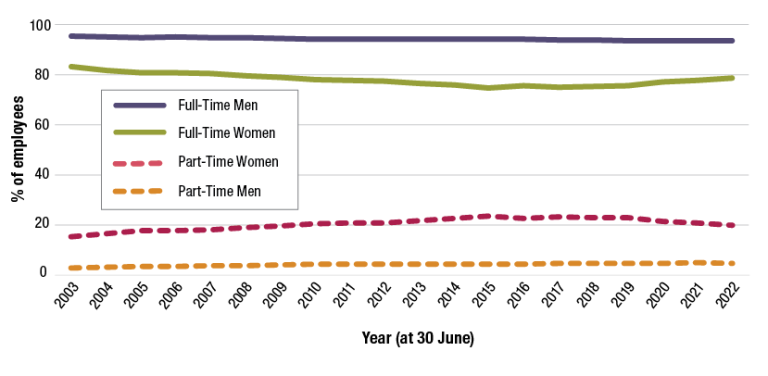

All APS employees should have equal choice when it comes to balancing work and caring responsibilities while being supported to pursue career opportunities. Over the past 20 years, the percentage of women accessing part-time work steadily increased but for men it remained largely unchanged (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12: Working hours by gender and year (2003 to 2022)

Source: APSED

Across the world, women were disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.[16] Rates of overall employment, hours of work, and the division of unpaid work at home were all affected. The situation in Australia was no different.[17] While the impacts on women were pronounced during the pandemic, the response to COVID-19 may ultimately offer opportunities for greater gender equality.

As the pandemic unfolded, employers offered more access to flexible working arrangements. The size and speed of this transition within Australia was unprecedented.[18] If managed well, this greater access to flexibility has the potential to increase gender equality and workforce participation of women, including in leadership roles. Through working from home, a greater number of men have experienced the demands associated with caring and domestic work. This has the potential to shift gender norms, at work and at home.[19]

Increased access to flexible working arrangements was one way the APS responded to COVID-19. These changes may ultimately see greater gender equality across the public service.

Gender equality reporting

Alongside implementing the APS Gender Equality Strategy, the APS continues to focus on gender equality by supporting the work of the WGEA.

Before the review of the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2021, the Australian Government committed APS agencies to report to WGEA from 2022–23. To prepare for this new annual reporting, the APSC has worked closely with WGEA to align data already collected through its existing reporting arrangements to WGEA’s reporting requirements. This demonstrates responsible data sharing and streamlines processes for all APS agencies.

A pilot involving five agencies was completed in 2021. The feedback was used to update elements of WGEA's reporting to align more closely to the public sector environment. In 2022, APS agencies were encouraged to report to WGEA on a voluntary basis, with more than 40 agencies participating and providing additional feedback on data collection and survey processes to further develop WGEA’s approach for the APS.

This valuable data collection process will allow the APS to benchmark progress on gender equality matters against other entities and compare progress against other industries. It will also help measure the participation of women in the workforce, measure the representation of women in leadership roles and help identify gender equality challenges for future action.

Footnotes

[16] T Alon et al., The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality, n.d., 2020.

[17] TW Fitzsimmons, MS Yates and VJ Callan, Experiences of COVID-19: The pandemic and work/life outcomes for Australian men and women, Brisbane: University of Queensland Business School, n.d., 2022.

[18] Productivity Commission, Working from home, 16 September 2021.

[19] T Alon et al., The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality, n.d., 2020.