Report on performance of statutory functions

Year-end totals for all reviews of action

During 2018–19 we received a total of 1,260 applications for a review of an APS action. Of these:

- 1,089 were applications for a promotion review

- 88 were applications for a primary review of a finding that an employee had breached the Code of Conduct, a sanction decision, or cases where it was not appropriate for the agency to conduct the initial review

- 77 were applications for a secondary review of an employment-related action (following dissatisfaction with the internal agency review)

- six were applications by former employees for review of a finding that they had breached the Code of Conduct or for an inquiry into entitlements on separation from the APS.

Figure 2: Trends in total number of review of action applications, 2015–16 to 2018–19

The number of promotion review applications can vary considerably from year-to-year, while primary and secondary reviews have remained relatively stable across time.

Reviews of promotion decisions

An ongoing APS employee can seek a review of an agency’s decision to promote one or more employees to an ongoing job at the APS 1 to 6 classifications. This is a merits-based review and, to be successful, the applicant must demonstrate that their claims to the job have more merit than the employee who was promoted.

Of the 1,089 applications for a review of a promotion decision we received during the year, 112 were applications from unsuccessful applicants for promotion.

A total of 82 Promotion Review Committees were formed to consider 392 promotion decisions.

Promotion Review Committees also consider applications from individuals who have been promoted but who apply for review of the promotion of another APS employee in the same selection exercise. These are sometimes referred to as ‘protective’ applications. Their purpose is to ensure the employee’s interests are protected if their promotion is overturned on review—that is, if their promotion is set aside by a Promotion Review Committee, their ‘protective’ application will proceed to review. In 2018–19, none of these ‘protective’ applications proceeded to review, either because no unsuccessful applicants from the same selection exercise sought review of their promotion, or there was a review and the Promotion Review Committee upheld their promotion.

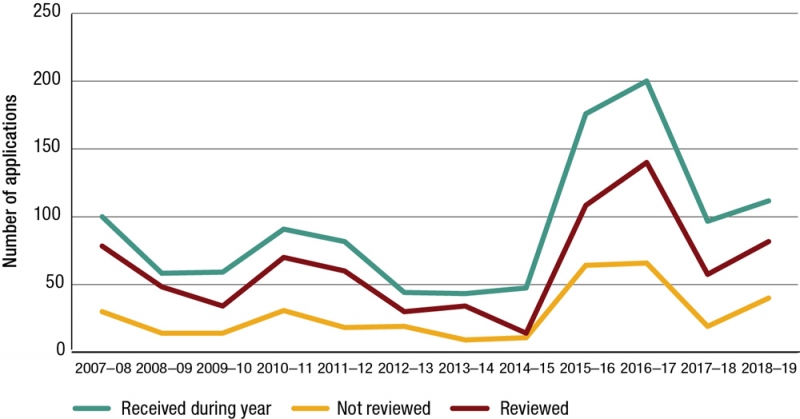

Figure 3 shows applications for promotion review from unsuccessful candidates, including how many did and did not proceed to review by a Promotion Review Committee. This shows the number has fluctuated between 2007–08 and 2018–19 (note: Tables 7 and 8 in the Appendix provide a more detailed breakdown of these applications and promotion review caseload).

Figure 3: Trends in applications for a promotion review from unsuccessful candidates considered by Promotion Review Committees, 2007–08 to 2018–19

In 2018–19 both the number of applications from unsuccessful applicants and the scale of promotion review exercises increased. This reversed a sharp decrease from the peaks in 2015–16 and 2016–17. These peaks were the result of a significant increase in recruitment activity in large agencies following the lifting of a freeze on recruitment.

The promotion review application rate increased by 15 per cent in 2018–19 following a fall of 45 per cent in 2017–18. We handled 112 applications from unsuccessful applicants in 2018–19 compared with 97 in 2017–18.

These applications related to review of promotion decisions in 11 agencies. Figure 4 shows the number of Promotion Review Committees established and finalised by agency, as well as the number of promotion decisions considered and the number of parties to a promotion review.

Figure 4: Promotion review parties, committees and decisions by agency, 2018–19

As highlighted in Figure 4, the majority of finalised promotion reviews were of promotion decisions made in the Department of Human Services (now called Services Australia) and the Department of Home Affairs.

A party to a promotion review is either an unsuccessful candidate who has applied for promotion review or the person(s) promoted. During 2018–19 the largest number of parties to a promotion review for a single recruitment exercise was 71. This compares with 38 in 2017–18. Nine other recruitment exercises had 10 or more promotion review parties, compared with six in 2017–18. There was also an increase in the average number of applications per recruitment exercise—6.1 in 2018–19 compared with 4.4 in 2017–18.

Promotion Review Committees varied two (0.51%) of the 392 promotion decisions reviewed. This is similar to the percentage of promotion decisions varied in 2017–18 (0.37%) and in 2016–17 (0.49%). When a Promotion Review Committee varies a decision, it means the committee determined on the basis of merit that a review applicant was more meritorious for the position than the APS employee recommended by the selection panel. In these cases the committee’s decision is determinative and final. Neither of the two promotion decisions varied involved protective applicants.

The performance target for conducting promotion reviews is that 75 per cent will be completed within either eight or 12 weeks of the closing date for an application, depending on the number of parties to a promotion review. That is, eight weeks for up to 10 parties and 12 weeks for 10 or more parties to a review.

We completed 95 per cent of promotion reviews within target timeframes during 2018–19. Four reviews were not completed within their target time of eight weeks, with only one case more than four days overdue. In this case the promotion review was delayed because a new committee needed to be formed after one member withdrew for unforeseen personal reasons.

Reviews of other actions

Reviews of other actions include:

- Primary reviews of a determination that an APS employee has breached the Code of Conduct, a review of a sanction decision, or a review where an internal agency review is not appropriate—in these cases the APS employee does not need to apply for an internal agency review before applying to the Merit Protection Commissioner.

- Secondary reviews of any other employment-related action—in these cases, the APS employee must seek an internal review by their agency before applying to the Merit Protection Commissioner.

These reviews often involve complex decision making and account for the bulk of the work undertaken by staff within the office.

Review caseload and finalisation

Figure 5 shows the trends in review casework in the past 12 years. The total figures have been relatively stable over the last few years, with a slight upward trend this year.

Note: See Table 2 in the Appendix for information on the number of applications for review (other than promotion review) received and reviews completed in 2018–19 compared with 2017–18.

In 2018–19 we received 171 applications for review, compared with 166 in 2017–18. We finalised 176 cases in 2018–19, including 40 cases carried over from 2017–18. A case is finalised when it is closed for one of the following reasons:

- following a full merits review

- because the application was ineligible or the action was non-reviewable

- because the application was withdrawn

- because the review right lapsed as the applicant left the APS.

Of the 176 finalised cases, 80 were subject to a full merits review. The remainder did not proceed or continue for the other reasons above. The following section provides further information on applications not accepted for review.

Of the matters decided by the Merit Protection Commissioner (that is, where we conducted a review or assessed the application as being ineligible), we finalised 79 per cent during the reporting period. This is an improvement on the previous year where we finalised 68 per cent.

The performance target for reviews of employment actions is that 75 per cent of reviews will be completed within 14 calendar weeks of receipt of an application (excluding time on hold). We exceeded our performance targets in the reporting year, with 82 per cent of review of employment action cases finalised within the target timeframe (compared with 77 per cent in 2017–18).

The average time taken to finalise a case was 10.6 weeks (excluding time on hold). When time on hold is included, the total average time to finalise cases was 17.7 weeks.

Review cases are put on hold when the review is not able to progress. The main reasons are:

- waiting for papers or information from the agency

- waiting for additional information from the applicant

- waiting for an agency to make a sanction decision (an application for review of a decision that an employee has breached the Code of Conduct may be placed on hold pending receipt of an application for review of the sanction arising from the same matter).[1]

Delays originating in our office, including the 8-day Christmas closure, accounted for a small amount of time cases were placed on hold. Time on hold is not counted against the 14-week performance target.

In 2018–19, on average 40 per cent of the time between the date an application was received and the date the review was finalised was spent on hold. The average time on hold for a finalised review increased slightly from 6.7 weeks in 2017–18 to 7.15 weeks in 2018–19.

Applications not accepted for review

In 2018–19, 25 per cent of applications were not accepted for review. This compares with 28 per cent in 2017–18. The reasons for not accepting applications varied according to the type of review.

The main reasons for not accepting applications for review of Code of Conduct decisions were:

- the application was received outside the timeframe for lodging a review

- the application concerned decisions other than a finding that the employee had breached the Code of Conduct or a sanction decision.

The main reasons for not accepting applications for review of employment action matters other than Code of Conduct decisions were:

- the Merit Protection Commissioner exercised discretion not to review a matter for various reasons, among them that nothing useful would be achieved by continuing to review the matter (28%)

- the applicant needed to first seek a review from their agency (26%)

- the application was about a matter that fell into one of the categories of non-reviewable actions set out in Regulation 5.23 or Schedule 1 to the Regulations (19%)

- the application was out of time (9%).

Generally, decisions not to accept applications for review are made quickly—just over half of these decisions are made in two weeks or less. Some decisions can take longer if the decision maker needs to clarify matters of fact with the agency or the review applicant. A total of 36 per cent took four weeks or more. The average time taken to decide to decline an application was just under five weeks.

[1] In the majority of cases the Merit Protection Commissioner will commence a review of a breach decision irrespective of whether a sanction decision has yet been made. In some cases the Merit Protection Commissioner will wait to commence a review of a breach decision (for example, when the sanction decision is about to be made or at the request of the applicant).

Case study 1: Further review of an employee’s concerns not justified as no useful outcome could be achieved

An employee sought review of their agency’s response to allegations made by a colleague about the employee’s behaviour, and allegations the employee made about the colleague’s behaviour. The background to this matter was historical conflict between staff of two teams whose functions overlapped.

The agency declined to investigate the employee’s allegations about the colleague. The agency engaged a consultant to investigate the colleague’s allegations about the employee, and a different consultant to conduct a review of the employee’s concerns about the investigation and the handling of his allegations. The employee was found to have behaved inappropriately in one incident. This finding was recorded on the employee’s personnel file but no other action was taken (for example, action under the performance management or misconduct frameworks).

The Merit Protection Commissioner declined to review the employee’s concerns on the basis that further review by either the agency or the Merit Protection Commissioner was not justified in the circumstances. The Merit Protection Commissioner gave the following reasons:

· No substantive adverse outcome for the employee arose from the agency’s handling of this matter.

· The employee’s allegations about the colleague concerned incidents that were several years old and arose from: workplace gossip; speculation about motives; and differences of opinion about the colleague’s authority. The Merit Protection Commissioner considered that further review or investigation was unlikely to prove or disprove the employee’s claims.

· The employee had not identified any outcome from further review that would assist in resolving the workplace dispute. In the Merit Protection Commissioner’s opinion, the employee wanted to be proven correct and this was an unlikely outcome.

The Merit Protection Commissioner noted that the staff involved in this dispute were relatively senior, and the workplace conflict was ongoing and appeared not to have been resolved by the agency’s interventions. The Merit Protection Commissioner suggested the agency incorporate behavioural expectations, including collaborative working, in the performance agreements of the staff involved in the dispute.

Number of reviews by agency

During the year we completed review of other actions in 18 APS agencies.

Figure 6: Review of action other (primary and secondary) by agency, 2018–19

Note: Table 4 in the Appendix provides greater details on the number of reviews by agency. ‘Other’ agency category is comprised of 13 agencies with less than four review applications for 2018–19.

In 2018–19 the Department of Defence accounted for 27.5 per cent of the completed reviews and the Department of Human Services accounted for 24 per cent. The Department of Home Affairs and the Australian Taxation Office together accounted for a further 19 per cent of reviews. This differs to 2017–18 when the Department of Human Services accounted for 52 per cent of completed reviews.

Case study 2: Applying a subjective test to an employee’s behaviour

An employee was found to have breached two elements of the Code of Conduct (respect and courtesy and upholding the APS Values) for a comment she made to a colleague during a conversation. The employee received sanctions of a reprimand and a small fine.

The review material indicated there was a history of conflict between the two employees, which the workplace was managing, including through alternative dispute resolution.

The finding of misconduct arose from a discussion between the employee and her colleague about a workplace matter. The employee was confused by what her colleague told her and made a comment about the colleague’s state of mind. The colleague subsequently complained that he found the comment offensive. His complaint was expressed in very strong terms and indicated that he had reflected on, and interpreted, what the employee had said.

The agency decision maker considered that the employee had engaged in misconduct for ‘causing offence’ to the colleague. The Merit Protection Commissioner concluded the evidence of what the employee had actually said was unclear. Nevertheless, even if the employee had said what was stated in the complaint, the words attributed to her could not reasonably be viewed as offensive or justify such a strongly worded complaint.

The Merit Protection Commissioner recommended that the finding of misconduct be set aside, noting that the test for establishing whether an employee has breached the Code of Conduct is an objective one (the reasonable person test). In this case, the agency decision maker appeared to have applied a subjective test by accepting the colleague’s characterisation of the employee’s behaviour without making an assessment of whether a fair minded, independent observer would view the employee’s words in this way.

Review outcomes

The Merit Protection Commissioner may recommend to an agency head that a decision be set aside, varied or upheld.

The majority of review of other actions result in the agency decision being upheld. In 2018–19 we upheld 71 per cent of agency decisions or actions in the 80 cases subject to full merits review. As shown in Figure 7, this is higher than the previous year (in 2017–18 we upheld 60 per cent) and similar to the 74 per cent upheld in 2016–17.

Figure 7: Number of agency actions or decisions set aside/varied or upheld, 2007–08 to 2018–19

In 26 per cent of cases we recommended the decision under review be varied or set aside. A further two per cent of cases resulted in a conciliated outcome.

Compared with other types of employment actions, we are more likely to recommend that Code of Conduct decisions be varied or set aside. In the reporting year, 36 per cent of determinations of misconduct or sanctions we reviewed were set aside or varied, compared with 38 per cent in 2017–18. This is higher than for our reviews of other action (that is, secondary reviews where the employment action has been first reviewed by the agency) where we recommended that 19 per cent be varied or set aside, compared with 24 per cent in 2017–18.

Two reviews related to findings that a former APS employee had breached the Code of Conduct. In one case, we recommended the agency decision be varied because one of four breaches was not found, while in the other we upheld the agency decision as it was fair and reasonable.

The main reasons the Merit Protection Commissioner recommends an agency misconduct decision be set aside are:

- procedural problems in the decision making process result in substantive unfairness to the employee

- insufficient evidence to determine that the employee had done what they were found to have done

- assumptions made without sufficient evidence.

The main reasons for recommending an agency misconduct decision be varied are:

- the employee has done only some of what they were found to have done

- the agency has misapplied elements of the Code of Conduct.

The main reasons for recommending other employment decisions (that is, secondary reviews) be set aside or varied are:

- substantial non-compliance with agency policies

- failure to afford procedural fairness in a fact finding inquiry

- insufficient evidence about performance expectations and of the level of performance required

- there has not been proper regard to the employee’s personal circumstances in applications for flexible working arrangements.

Thank you for your detailed review. We will take learnings from this matter, including the need for managers to maintain contemporaneous notes [of performance discussions] and clarify directly with the employee when they feel an employee is falling short.

Agency manager—May 2019

Two cases were conciliated during the reporting year, one involving separation entitlements and the other a request for a primary review of the actions of a supervisor. In these cases, the agency or review applicant agreed to act on the Merit Protection Commissioner’s preliminary view about an employee’s case without the Merit Protection Commissioner making a formal recommendation. By the end of 2018–19, agencies had accepted all our review recommendations. Three agency responses were outstanding at 30 June 2019.

Case study 3: Agency’s operating environment a relevant consideration in setting sanctionA level of consistency in sanctions for similar behaviour is desirable across APS agencies. However, because of their operating environment, some agencies view particular behaviours more seriously than might generally be the case.

Integrity agencies with staff employed under the Public Service Act demand the highest standards of integrity and professionalism from their staff because of the nature of their work, the sensitive information they hold and the risk of staff being compromised. These standards are reinforced through processes such as employment suitability screening and integrity testing.

Two employees from different integrity agencies were reduced in classification as a result of a finding of a breach of the Code of Conduct. Both employees argued on review that the sanction they received was unfair, including because the sanction was disproportionate to the objective seriousness of the behaviour.

One employee identified himself on social media as an employee of the agency, in breach of the agency’s social media policy, engaging in behaviour that his employer would not approve of. A second employee failed to record her attendance accurately over a six month period accruing a debt to the Commonwealth.

The Merit Protection Commissioner had regard to the sanction decision makers’ views of the trustworthiness of both employees. In the first case, the employee was a supervisor and his behaviour demonstrated a lack of mature professional judgement. In the second case, the employee did not demonstrate an intrinsic motivation to do the right thing. The Merit Protection Commissioner also considered the leadership and accountability standards for the employees’ classification levels outlined in the APS Work Level Standards.

The Merit Protection Commissioner also considered the need for general deterrence—that in these cases the sanctions demonstrated to agency employees more generally that these behaviours were not tolerated. The Merit Protection Commissioner recommended the sanctions be confirmed.

Reviews by subject matter (excluding Code of Conduct)

As noted elsewhere, reviews of actions (excluding Code of Conduct matters) are typically secondary reviews where the applicant must have sought an internal review by their agency before applying to the Merit Protection Commissioner. Figure 8 (below) and Table 5 in the Appendix provide a breakdown of secondary review cases by subject matter, excluding Code of Conduct reviews. The majority of reviews relate to same three areas of concern as in 2017–18, that is, performance management, workplace behaviour and access to flexible working arrangements.

Figure 8: Cases reviewed by subject matter, 2018–19

Note: Excludes Code of Conduct cases.

Case study 4: Review of a performance rating and process

An employee disputed a performance rating of ‘not on track’ based both on his output and behaviours. The employee also claimed that his manager was treating him unfairly and his agency had breached his workplace rights in the way he was managed during the performance cycle.

The employee’s performance agreement was goals focused and included no performance expectations. The employee drafted his agreement including only his career goals and his aspiration to pursue a career outside the agency. However, the Merit Protection Commissioner was satisfied that the employee was aware of the performance expectations in his role. The team he was part of had a team expectations document that covered outputs and behaviours.

There were documented discussions between the employee and his manager on the level of output expected and the manager’s concerns about the employee’s output. The employee disputed that the output expected was reasonable. The Merit Protection Commissioner gave weight to the manager’s views, as the manager was accountable for the performance of the team. In addition, the documentary evidence of the way the manager explained the requirements to the employee, and responded to his concerns, did not suggest the manager’s requirements were unfair or arbitrary.

The Merit Protection Commissioner was also satisfied that the manager’s concerns about the employee’s behaviour were valid. The employee displayed a lack of judgement in his email communications with his colleagues and managers, and in his personal behaviour in the workplace. In the Merit Protection Commissioner’s view, the employee’s behaviour was inconsistent with the behavioural requirements for the team, which included collaborative working and respect for colleagues.

The Merit Protection Commissioner observed that, as evidenced by email communications, the manager had responded to the challenges involved in managing the employee with professionalism, patience and courtesy. The Merit Protection Commissioner found the outcome of the performance management process was fair and complied with the agency’s policy framework, and that the employee’s manager had treated him fairly in assessing and rating his performance.

Code of Conduct reviews

APS employees who are found to have breached the Code of Conduct can apply to the Merit Protection Commissioner for a review of the breach finding and/or the sanction imposed. Our review work for Code of Conduct matters provides APS employees with an independent review of an action that is of significance for them. It is also an area of employment decision making that requires monitoring and a degree of oversight.

Data in the Australian Public Service Commissioner’s annual State of the Service Report for the past three years shows the Merit Protection Commissioner is estimated to review between 4 and 10 per cent of agency Code of Conduct decisions.[3] In 2018–19, Code of Conduct cases accounted for 45 per cent of all cases reviewed. Code of Conduct cases had been growing as a proportion of the total caseload (excluding a reduction to 39 per cent in 2017–18).

Figure 9: Trends in proportion of Code of Conduct reviews, 2012–13 to 2018–19

During 2018–19 there were 75 applications for review of a decision that an employee had breached the Code of Conduct and/or the sanction received, and 18 cases on hand on 1 July 2018. We finalised 36 cases during the year, involving 26 employees.[4] We also reviewed two applications by former employees for review of determinations that they had breached the Code of Conduct.

Of the 28 cases reviewed (26 current employees and two former employees):

- the decisions were upheld in their entirety in 17 cases

- we recommended the finding of misconduct be set aside in its entirety in four cases

- we recommended that the findings of breach be varied in five cases

- we upheld the breach decision but set aside the sanction decision because of procedural flaws in one case

- we varied the finding that the employee had breached the Code of Conduct but upheld the sanction decision in one case.

We recommended the findings of misconduct be set aside in four cases for the following reasons:

- In one case the employee who worked in an IT security role was found to have breached the Code for inappropriate use of IT resources for gaming, excessive use of Wi-Fi and failure to retain a password that would enable the agency to do a forensic search. We found the agency made assumptions about the employee’s activities on insufficient evidence and that the agency policy guidelines did not specify the obligations of staff in specialist IT security roles with respect to password maintenance.

- In one case the agency investigation failed to provide procedural fairness. The employee was provided with a summary rather than the full report into his conduct, thereby withholding credible, relevant and significant evidence.

- In one case the employee had done what the agency accused them of but the agency did not establish that the actions were in breach of the agency’s principles-based policy.

- In the final case the employee was found to have engaged in unacceptable personal misconduct in a conversation in the workplace. We found on review that it could not be established what had happened and the complainant's account was neither reliable nor objective. We also found other errors in the decision, such as the use of a subjective, rather than objective, test for establishing a breach and an unenforceable direction.

Case study 5: Failure to give a fair hearing

An employee was found to have breached two elements of the Code of Conduct (respect and courtesy and upholding the APS Values) for his behaviour towards a colleague during a work meeting.

The agency engaged an investigator who interviewed witnesses and prepared an investigation report with findings and recommendations. Because of privacy concerns about the witness evidence, the agency decided to provide the employee with an appendix to the report, which outlined the evidence with respect to the incident, but not the full report. In doing so the agency withheld information in the investigation report, including the witnesses’ and investigator’s opinions about the employee’s general behaviour and witness evidence about the employee’s previous behaviour towards the colleague. The agency considered this information was not relevant to the specific facts that needed to be determined, namely the employee’s behaviour during the incident.

The Merit Protection Commissioner considered that some of the information withheld from the employee was adverse information relevant to the finding of misconduct. The information indicated the employee had a tendency to behave in the way alleged in the incident. The Merit Protection Commissioner concluded that the employee should have been given an opportunity to comment on this information, or a reasonable summary of it, before the decision was made.

The Merit Protection Commissioner considered that the agency’s failure to give the employee a hearing about this information represented a substantive breach of the requirements of procedural fairness and recommended that the Code of Conduct breach determination be set aside on the basis of a serious procedural defect.

Figure 10 (below) and Table 6 in the Appendix provide a breakdown of the types of employment matters dealt with in Code of Conduct reviews.

Figure 10: Code of Conduct cases reviewed, by subject, 2018–19

The largest area of behaviour reviewed as misconduct concerned bullying and discourteous behaviour. The percentage of cases increased this year to 33 per cent, from 24 per cent in 2017–18. In most cases the behaviour was directed at colleagues or managers. However, in two cases managers directed the behaviour at their respective teams.

The conflict of interest matters reviewed concerned employees supporting a friend’s business and failing to declare a conflict of interest, using their position with agency clients in such a way as to seek advantages, and being involved in a recruitment exercise where a family member was selected. The social media matter reviewed concerned the employee involving a junior colleague in filming themselves in the workplace and then posting the video on Facebook in breach of the agency’s social media policy.

Case study 6: A flawed bullying and harassment investigation

Complaints were made about an employee’s behaviour in the workplace. The agency responded with a bullying and harassment investigation rather than a misconduct inquiry. The investigation was undertaken under the agency’s policy for responding to complaints of bullying and harassment.

The agency advised the employee that the investigation process was informal and on review, in response to the employee’s concerns, advised that the process did not have strict procedural fairness requirements.

The investigation resulted in adverse findings about the employee’s behaviour. These findings resulted in the employee being issued with a direction with respect to their future behaviour and the denial of performance-based salary advancement.

The Merit Protection Commissioner concluded that the way the investigation was conducted (including terms of reference, interviewing witnesses and taking statements, and developing a report with recommendations) meant the process was a structured and formal workplace investigation, not an informal tool to assist management decision making.

The Merit Protection Commissioner found the investigation process and final decision were procedurally flawed, including for the following reasons:

- The employee was told specific processes relating to the investigation would be followed and they were not

- The investigator did not supply the employee with a copy of the investigation report with findings or an opportunity to comment before giving the report to the decision maker

- The decision maker did not inform the employee of their proposed decision, or the evidence to support the decision, before issuing the behavioural instruction.

The Merit Protection Commissioner recommended the decision be set aside and a fresh investigation be conducted by people with no connection to the matter.

Consistent with the APS Employment Principles, employees are entitled to have fair decisions made. Processes in the workplace that have an investigatory character are workplace investigations. An employee should be notified of the process to be undertaken, and that process should be followed. Employees are entitled to procedural fairness in workplace investigations and, consistent with the hearing rule, should be given an opportunity to rebut any evidence, statement or proposed finding that is adverse or prejudicial to them, before these findings are presented to the decision maker.

Other review-related functions

Under Part 7 of the Public Service Regulations, the Merit Protection Commissioner may:

- investigate a complaint by a former APS employee that relates to the employee’s final entitlements on separation from the APS (Regulation 7.2)

- review a determination that a former employee has breached the Code of Conduct (Regulation 7.2A)

- review the actions of statutory officeholders who are not agency heads (Regulation 7.3).

Table 2 in the Appendix provides information on the number of applications made under Part 7 in 2018–19. We received five applications about final entitlements. Four applications were not accepted. In the fifth case, we resolved the former employee’s concerns through discussion with the agency, which decided to make the payment in dispute.

During the year we also finalised two applications from former employees for review of determinations of misconduct made after they had ceased APS employment. We upheld one case relating to failure to declare a conflict of interest. The second case involved four incidents of discourteous behaviour in the workplace. We found misconduct in three of the incidents, but noted that the fourth incident did not meet the threshold of seriousness to constitute misconduct.

There were no cases seeking review of the actions of a non-agency head statutory office holder.

Feedback from review applicants

All applicants with a completed review were given the opportunity to provide anonymous feedback to the Merit Protection Commissioner through an online survey. Applicants whose reviews were finalised between July and December 2018 were surveyed in February 2019 (noting the delay was because the survey instrument was being reviewed and updated). Applicants whose reviews were finalised in 2019 were usually surveyed within two weeks of receiving advice about the outcome of their review.

The response rate for the survey was 26.5 per cent (18 respondents). This compares with 37 per cent in 2017–18 and 18 per cent in 2016–17.

The feedback shows that 50 per cent of respondents found out about their review rights from the Merit Protection Commissioner website. The next most significant source of information was their agencies. Two-thirds of applicants agreed the Merit Protection Commissioner website was easy to navigate, a further 17 per cent did not agree, and 17 per cent were neutral. Suggestions for improving the website included providing a clearer explanation of the process, the scope of reviews and expected timeframes, as well as greater use of case summaries.

There was general satisfaction with the application process. The majority of respondents found:

- the application forms were easy to lodge (72%) and easy to fill in (89%)

- the information sheet provided to them after they made their application was the right length, contained the information they needed, and was relevant and easy to follow and understand (80%).

On contact and dealings with Merit Protection Commissioner staff, approximately three-quarters of respondents reported that they were advised of who they should contact in the office (78%), received adequate information at the beginning of the review to understand how the review would proceed (72%), had their phone calls and emails responded to in a timely manner (78%) and were given the opportunity to submit information supporting their review application (72%).

However, only two-thirds of respondents reported that they were given appropriate information about the scope of the review, and only half considered they received enough updates about the progress of their review. In addition, only half considered they understood what information they needed to provide in their written submission.

Of the 16 applicants who could recall, 56 per cent (nine) were told how long the review would take and 56 per cent of these reviews were completed within that timeframe.

The above results suggest that at the beginning and throughout the review process, we need to provide applicants with better information about the contact point in the office, the scope of their review, what information is needed (and what is not required), what they can expect to achieve, and the expected timeframes. This will be an area of focus in the coming year.

When it came to feedback on the outcome and satisfaction with the review process, the views of respondents are generally polarised, correlating with their satisfaction with the outcome. Only 39 per cent thought the review was completed in an independent and impartial way, and 44 per cent thought the review process was fair and equitable. A total of 56 per cent stated they would recommend the process to a colleague.

I am very appreciative of the time you have spent going through the whole matter, sourcing all the facts necessary and allowing me to provide my views.

Review applicant—March 2019

The reasons for the negative responses included:

- failure by the Merit Protection Commissioner’s office to invite submissions, contact the applicant in person, or allow them to respond to submissions/preliminary view in a similar timeframe given to agencies

- not addressing the applicant’s concerns

- the applicant’s perceptions that the agency’s submissions and views were given greater weight than their views

- the applicant’s perception that the process was biased and favoured the agency, which had more resources

- the process was not timely.

Three of the respondents in particular were very disparaging of the Merit Protection Commissioner and their experience of the review process (for example, describing it as ‘a waste of time’, ‘my claims [were] condescendingly dismissed out of hand by your biased and partisan Reviewer’). However, the six respondents who indicated their outcome was a set aside were highly supportive of the review process. Their views on the decision letter/report were all positive and they considered the process to be fair, impartial and unbiased, and would recommend the process to a colleague.

I would like to compliment your team member…in relation to her interaction with me when advising me of the outcome of a recent matter…While it wasn’t the outcome I wanted, the way in which [team member] contacted me and spoke to me was far greater than anything I expected from an Australian Government employee.

Review applicant—July 2019

Some of the survey responses suggested the need for improvements in relation to a number of procedures and practices. These included having a greater degree of personal contact with the applicant (and for some applicants, any contact at all), clearer pathways for lodging applications, providing better advice on the scope and timing of the review, and providing progress reports. We will address these matters during 2019–20.

Inquiry functions

Under section 50(1)(b) of the Public Service Act, the Merit Protection Commissioner may:

- inquire into public interest disclosures (within the meaning of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013) relating to breaches of the Code of Conduct

- inquire into complaints that the Australian Public Service Commissioner has breached the Code of Conduct and report on the results of any inquiry to the Presiding Officers of the Parliament, including any proposed sanction

- at the request of the Public Service Minister, inquire into an APS action.

Provisions were inserted into the Public Service Act to enable the Merit Protection Commissioner to inquire into public interest disclosures. However, the Commissioner was not prescribed in the Public Interest Disclosure Rules as an authorised officer, so agencies are unable to refer disclosures to her. The Merit Protection Commissioner may inquire into a disclosure if the disclosure was made to an agency head and the discloser is not satisfied with the outcome. We finalised one such application for an inquiry in 2018–19.

The applicant made a disclosure to their agency. The matter was investigated, however, the applicant considered that the agency head may not have implemented appropriate measures under the Code of Conduct. The Merit Protection Commissioner considered the request and sought further information. The Commissioner declined to inquire into the disclosure, as she was of the opinion that any inquiry would be unlikely to result in any recommendation to the agency to undertake action under the Code of Conduct.

Two complaints that the Australian Public Service Commissioner had breached the Code of Conduct were under investigation at the start of the reporting year. Both matters were concluded on 7 August 2018, when the Merit Protection Commissioner provided the final report to the Presiding Officers of the Parliament.

There was no request from the Public Service Minister to inquire into an APS action during 2018–19.

Statutory services provided on a fee for service basis

Inquiries into breaches of the Code of Conduct

Under section 50A of the Public Service Act, the Merit Protection Commissioner may inquire into and determine whether an APS employee or a former employee has breached the Code of Conduct, if a request is made by the agency head. The inquiry must have the written agreement of the employee or former employee. The Merit Protection Commissioner charges a fee for inquiries done under this section.

Three cases were received during the reporting year. Two cases were withdrawn because the employee did not consent to the inquiry. An inquiry commenced into the third case but was not finalised on 30 June 2019. This matter involved allegations of bullying.

Table 9 in the Appendix sets out further information on inquiries by the Merit Protection Commissioner under section 50A for 2018–19.

Independent Selection Advisory Committees

If requested, the Merit Protection Commissioner may establish Independent Selection Advisory Committees to help with agencies’ recruitment processes. These committees are independent three-member bodies that perform a staff selection exercise on behalf of an agency and make recommendations about the relative suitability of candidates for jobs at the APS 1 to 6 classifications. The convenors are employees working for the Merit Protection Commissioner.

Agency demand for the committees was lower in 2018–19, with only one agency requesting the use of Independent Selection Advisory Committees, compared with three in 2017–18. However, the recruitment exercise was large, covering a recruitment campaign for APS 6 vacancies in 11 locations in five states. Five committees were established. They considered 877 candidates and recommended 131 candidates for engagement, transfer or promotion—an average of 175 candidates and 26 recommendations per committee, compared with an average of 39 candidates and eight recommendations in 2017–18.

As the national campaign involved different committees, we worked with the agency and the convenors before the selection process commenced to ensure a consistent approach. We also held regular meetings with the convenors to address common issues including the handling of applicants who applied for multiple vacancies across the states.

Table 10 in the Appendix provides information on Independent Selection Advisory Committee activity for 2018–19, compare with to 2017–18.

Non-APS fee for service work

In accordance with Regulation 7.4, the Merit Protection Commissioner can offer other fee for service activities, such as staff selection services and investigating grievances, to non APS-agencies. No work was carried out under Regulation 7.4 during 2018–19.

[3] The State of the Service Report 2017–18 reported 569 employees were found to have breached the Code of Conduct in 2017–18. In 2017–18 we reviewed applications from 23 employees relating to breaches of the Code of Conduct and a further 18 were on hand. While the two sets of data do not include the same employees, a comparison over time provides an estimate that between four to 10 per cent of agency decisions are reviewed.

[4] Employees may apply separately for a review of a breach determination and the consequential sanction decision. Where this happens, it is counted as two cases, as each is a review of a separate action. This is the reason there are more cases than employees.