Chapter 2: Transparency and integrity

Key points

- Public trust in governments in many countries, including Australia, is in decline.

- Increased transparency and more effective engagement with the community, especially in the co-design and implementation of services and policies, is a priority.

- All agencies reported that the APS Values were reflected in their management practices and procedures.

- Most APS employees agreed their colleagues, supervisors and senior leaders ‘always’ or ‘often’ act in accordance with the APS Values.

- A total of 569 employees were subject to an investigation into a suspected breach of the APS Code of Conduct that was finalised in 2017–18. This equates to 0.4 per cent of the APS workforce.

- The rate of perceived bullying and/or harassment in the APS has been declining since 2015.

- In 2018, 12 per cent of employees perceived discrimination at work in the past year.

Public trust

Trust in government is declining in many countries. Trust is important for ensuring success of government programs. ‘Lack of trust compromises the willingness of citizens and business to respond to public policies and contribute to a sustainable economic recovery.’7

Trust can be influenced by citizens’ experiences in receiving government services, citizen engagement and inclusive policy design, appropriate regulation and integrity of institutions.

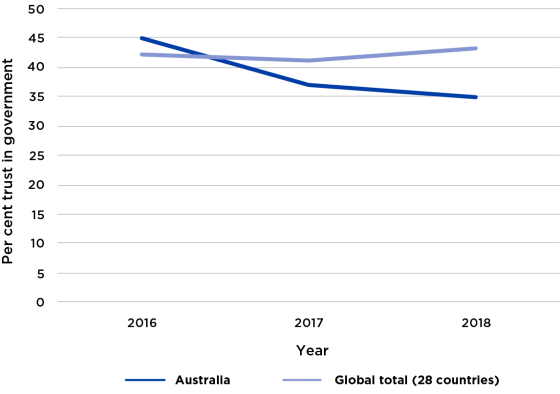

There are many global measures of trust in government. One of the most long-standing is the Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual online survey of trust in 28 markets around the world.8,9 In 2018, the Edelman Trust Barometer showed that in Australia, citizen trust in all levels of government institutions has continued to decline.

Australia ranked 19th across the 28 countries assessed, with an overall score of 35 per cent trust in all Australian governments. Australia’s ranking reflects all three levels of government and is well below the average of 43 per cent, falling within the barometer’s ‘distrust’ range.

The loss of trust in government often comes when there’s a loss of trust in the capacity of people to deliver services. That translates I think more broadly to us in the federal or state sphere where we’re trying to policy advise even where we’re not directly delivering services, if they cannot trust that a) we have the expertise to deliver, or b) that we’ve engaged them seriously along the way.

Dr Steven Kennedy PSM, Secretary, Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development10

Figure 4: Edelman Trust Barometer—trust in government institutions (all levels of government)

Source: 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer

In the 2017 Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey11 undertaken by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, the Australian community was asked how trustworthy they considered 14 types of organisations. Federal, state and territory public sectors achieved the third highest rating (58 per cent).

In terms of how public servants build the public’s trust, it comes down to how we talk with the public, how we treat them, and how we ensure that we provide, rationally and without advocacy, the information they want and need to make informed judgments and decisions.’

Dr Gordon de Brouwer PSM, Former Secretary, Department of the Environment and Energy12

Transparency

Openness of government, transparency around decisions, and management of information are all key drivers of public trust.

The 2015 World Justice Project Open Government Index13 ranked Australia 9th out of 113 countries. The Index uses four dimensions to measure government openness: publicised laws and government data; right to information; civic participation; and complaint mechanisms.

Open Government National Action Plan

Australia’s first Open Government National Action Plan14 was launched in December 2016. It contained 15 commitments to advance public and private sector integrity, modernise access to government information and data, and digitally transform government services in Australia.

Under this plan, a new Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code was legislated and an International Open Data Charter adopted to strengthen the underlying frameworks for data usage. A Digital Marketplace and associated live dashboard have been implemented to give service providers greater access to Australian Government information and communications technology (ICT) procurement and improve public oversight of government services. Substantial progress has been made in improving the discoverability of government data.

On 21 September 2018, the second Open Government National Action Plan 2018–2020 was released.15 The plan was developed using an extensive co-design and consultation process between government, members of the Open Government Forum and the community. The plan comprises eight targeted commitments that will further open up government and help realise the values of the Open Government Partnership. These values include enhancing access to information, civic participation, public accountability, and technology and innovation for openness and accountability.

Specific commitments include exploring ways the government and the public service can adopt more place-based approaches in its work; involving the states and territories in the promotion of Open Government Plan values and principles; and enhancing the ability for the public to engage in the work of the public service.

Use and transparency of government data

Of key importance to public trust is transparency and openness around the use of the data and information collected by governments.

As recognised in Australia’s second Open Government National Action Plan 2018–19 and by the Productivity Commission’s 2017 report Data Availability and Use, government data offers significant opportunity for innovation and research.16 Commitments through the second Open Government National Action Plan 2018-20 reinforce the Government’s existing policy to have non-sensitive data open by default.

2018 Review of Australian Government Data Activities

The 2018 Review of Australian Government Data Activities17 found:

- improvements in access to public sector data

- agencies using data more efficiently to provide agile and effective services

- public sector data skills and capabilities improving

- government data protections are building citizen trust and confidence in how public sector data is collected and used.

In response to the review, the Government intends to introduce a Data Sharing and Release Bill as part of its commitment to reforming data governance.

The intent of the new legislation is greater realisation of the economic and social benefits of increased data use, while maintaining public trust and confidence in the system.

The Government has established the Office of the National Data Commissioner, with the statutory appointment of a commissioner pending the passage of the Data Sharing and Release Bill. The National Data Commissioner will be responsible for implementing a simpler data sharing and release framework that will break down the barriers preventing efficient use and reuse of public data. The framework is designed to ensure that strong security and privacy protections are in place.

Citizen engagement

Citizen engagement is critical in establishing the public’s trust in the decisions the APS makes, including agency advice to government.

Citizen engagement provides the APS with access to a significantly wider scope of ideas and experience from the public who are directly impacted by new and existing policies and services.

Citizens can help the APS develop a greater understanding of issues and enable the development of policies and services that will address actual, not assumed, needs.18

Placing citizens at the centre of policymaking and service design ensures they have the opportunity to help shape policy and services in the areas that matter to them.

Research into citizen engagement19 has highlighted the benefits that can be realised when government builds strong and open relationships with the public it serves, including:

- improving the quality of policy being developed, making it more practical and relevant, and ensuring that services are delivered in a more effective and efficient way

- providing the government with a way to check the health of its relationship with citizens directly

- revealing ways in which government and citizens can work more closely on issues of concern

- giving early notice of emerging issues, putting government in a better position to deal with these in a proactive way

- providing opportunities for a diversity of voices to be heard on issues that matter to people

- enabling citizens to identify priorities and share in decision making, thereby assuming more ownership of solutions and more responsibility for their implementation

- fostering a sense of mutuality, belonging and a sense of empowerment, all of which strengthens resilience.

Genuine citizen-centric approaches to policy and service delivery require more than just consultation to elicit information and opinions.

How confident are we that we know our fellow citizens? For private sector organisations, success depends on knowing their customer base intimately: knowing what they want before they know it themselves. Our clientele is the entire population of Australia. How well do we know what they want, what they think, how they engage and make decisions, what shapes and drives their daily interactions?

- Dr Martin Parkinson AC PSM, Secretary—Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet20

In the 2018–19 Budget, the Government committed to driving more effective engagement between public sector officials, citizens, businesses and innovators when designing and delivering policies, programs and services.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs—MyService Pilot

At the start of its transformation journey, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) started a project to make client registration, service access and compensation claims for veterans faster and simpler. Applying the Digital Service Standard, the project team conducted deep-dive interviews with clients, employees and advocates as part of the discovery phase around the Initial Liability Claim process.

The objective of the engagement was to ensure DVA understood the problem from the client’s perspective. DVA needed to know:

- what users are really trying to do when interacting with the department

- their current experience

- what their needs are.

Key insights were recorded and from this key themes emerged. A number of client ‘personas’ were developed against which proposed solutions could be tested.

Through this direct engagement process, DVA realised that a claim is merely a means to an end. The clients DVA spoke to were mostly trying to access treatment to be healthy and productive in their civilian life. Some needed financial assistance but most had long careers ahead of them.

While DVA is there to help support these clients with services, including health care and rehabilitation, the department learned that the previous claims process was a burden on the client, at times leaving them feeling confused and deflated and, in some instances, even questioning their worth as a veteran.

This led to a change in hypothesis from faster, easier claims to ‘How might we help those who have served to be healthy and productive?’ This philosophy drives the MyService approach.

The co-designed service is showing real benefits for veterans and average processing times have reduced from 117 days to 33 days during the initial MyService trial. The MyService trial was undertaken as part of the $166 million Veteran Centric Reform work announced in the 2017–18 Budget.

The APS is beginning the journey of eliciting and analysing overall citizen experiences and perceptions on the breadth of services delivered to the Australian public by the Australian Government.

Individual agencies undertake a range of client/customer surveys to gather agency and/or transaction-specific information. A regular, non-partisan citizen survey focused on citizen experiences and engagement broadly across the APS should enable better policy development and improved service delivery.

Measuring to enhance citizen engagement—The Citizen Survey

At the opening of Innovation Month in July 2018, the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Dr Martin Parkinson AC PSM, announced the development of a regular, national survey that measures citizen satisfaction, trust and experiences of the APS.

The announcement builds upon the recommendation made by Terry Moran AC in the 2010 public sector reform blueprint, Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for the Reform of Australian Government Administration.

The survey will align with the mechanisms many agencies undertake to understand user satisfaction in their services and fill an important gap. It will provide an opportunity to consistently understand the public’s overall experiences and perceptions of the diverse range of APS services.

By better understanding citizen attitudes and satisfaction with the APS, results will be able to support continued improvement in service delivery and contribute towards a citizen-centred APS culture.

Across the world, in Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand and at home in several Australian states and territories, this kind of citizen engagement has produced significant value.

Work is underway to engage widely and frequently. Extensive engagement will ensure a robust, valid and useful design and will create results that drive positive change.

The Department of Human Services—understanding the customer experience for students

The Department of Human Services is progressively transforming its student payment systems by learning directly from students about how they use its services and redesigning them around their needs. In 2017–18, this resulted in more than 45 online and behind-the-scenes improvements making it easier for students to claim and manage their payments. A significant amount of research was undertaken to guide the student transformation work, including engaging employees and students at universities and technical and further education campuses across South East Queensland to test and trial new processes.

As an example, in March 2018 the multidisciplinary team driving this project held student engagement sessions in the department’s Design Hub in Brisbane. A range of students participated in activities to help design, test and validate proposed changes. They each described their individual experiences of claiming student support payments.

Jenna told the Department of Human Services how her experience of dealing with the department had improved dramatically following online improvements such as reducing the number of claim questions from 117 to 37. Her original claim, in 2015, for Youth Allowance took four months to process and required many phone calls and visits to Centrelink. The inconvenience of having to supply multiple documents in hard copy turned to frustration when some were misplaced and she eventually had to resupply them. Jenna received ‘ambiguous’ advice on how long her claim would take to process and had to follow up because progress updates were not clear. Overall, Jenna said the process was ‘quite painful’.

In contrast, when Jenna re-applied for Youth Allowance in January 2018, she was surprised by how easy and simple it was to claim saying: ‘It took me five minutes to put it all through. I think a lot of information was populated from my last claim, so I just had to put in my new course and my start and finish dates. I found out within a day that I had got the claim put through, so it was very good after my first experience.’

Jenna is one of thousands of students who have benefited from the department’s student payment transformation work and the direct and ongoing involvement of students in all stages of the design process.

APS Values and integrity

The Public Service Act 1999 (Cwlth) (the Act) imposes obligations on all APS employees to demonstrate high levels of personal integrity. The APS Values and Code of Conduct establish mandatory standards of behaviour.

Agency heads are responsible for upholding and promoting the APS Values and ensuring compliance with Code of Conduct. Senior Executive Service (SES) employees are required to promote the Values, including by personal example. APS employees are required—at all times—to uphold the Values, the integrity and the good reputation of the employee’s agency and the APS.

Figure 5: APS Values

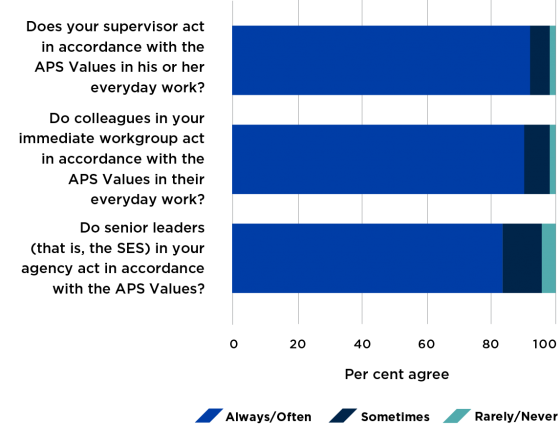

The annual APS employee census tracks employee views about the strength of compliance with the integrity framework.

In 2018, most APS employees agreed that their colleagues, supervisors and senior leaders ‘always’ or ‘often’ act in accordance with the Values in their everyday work.

Figure 6: Acting in accordance with APS Values

Source: 2018 APS employee census

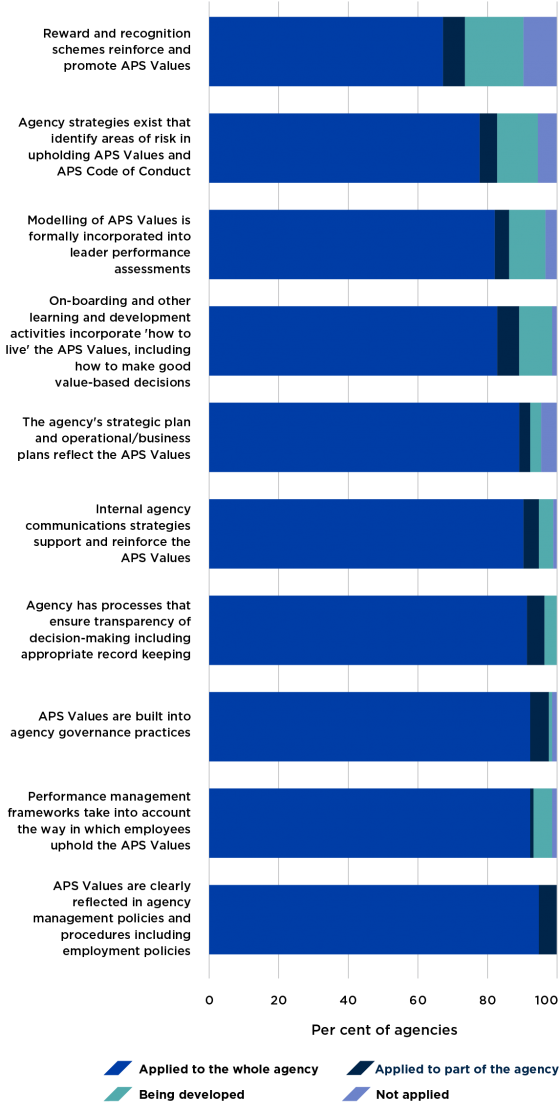

Agencies are committed to embedding the APS Values. In the 2018 APS agency survey, all agencies reported that the Values were reflected in their management practices and procedures, at least in part, if not throughout, their whole agency. Similarly, most agencies have ensured that performance management frameworks account for the way in which employees uphold the APS Values.

Figure 7: Measures applied by APS agencies in 2017–18 to embed the APS Values

Source: 2018 APS agency survey

The 2018 APS agency survey asked each agency to describe the most effective strategy used to embed APS Values. The most common strategies cited included:

- Embedding the APS Values in performance management frameworks. As part of the performance assessment process, managers are required to consider whether employees uphold and model APS Values. This ensures that managers and employees have regular conversations about the APS Values and how they apply to specific roles and day-to-day work. Incorporating the APS Values into performance management frameworks was also said to encourage greater employee accountability for upholding the Values.

- Incorporating APS Values into induction programs for new starters. Induction programs are generally delivered as online modules. Agencies described this mode of delivery as an effective strategy for embedding APS Values because it provides new employees with an introduction to the Values and the role they play in guiding behaviour across the APS.

- Offering training courses on APS Values and their practical application to employees. While most agencies delivered courses online, a few offered face-to-face workshops. Some courses were mandatory, while others were voluntary.

Managing misconduct

The APS has a strong framework for dealing with action or behaviour by employees which breaches the APS Values and the Code of Conduct. Misconduct can vary from serious actions such as large-scale fraud, theft, misusing clients’ personal information, sexual harassment and leaking classified documentation, to relatively minor actions such as a single, uncharacteristic angry outburst.

Instances of misconduct are rare. The vast majority of APS employees behave appropriately in the conduct of their duties.

The APS Values and the Code of Conduct ensure that the APS is well-placed to maintain the integrity of the service, strengthening the trust of citizens and the confidence of government.

APS Code of Conduct

The APS Code of Conduct clearly outlines expected behaviours of all APS employees, including the requirement to behave honestly and with integrity in connection with their employment. The Code of Conduct requires all APS employees at all times to behave in a way that upholds the integrity and good reputation of their agency and the APS.

A breach of the Code of Conduct can result in sanctions ranging from a reprimand to termination of employment.

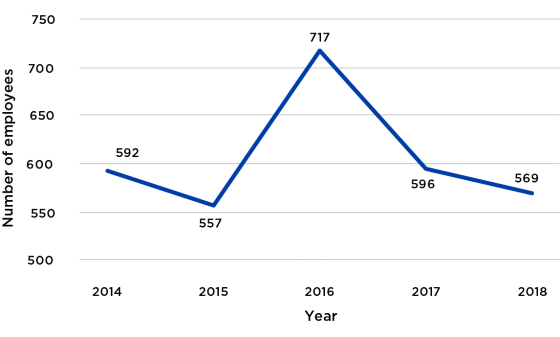

In the 2018 agency survey, agencies reported that 569 employees were subject to an investigation into a suspected breach of the APS Code of Conduct that was finalised in 2017–18. This equates to 0.4 per cent of the APS workforce.

Figure 8: Number of employees investigated for a suspected breach of the APS Code of Conduct, 2014–18

Source: 2018 APS agency survey

Of the employees investigated, 59 per cent were found in breach of the Code and a sanction was applied.

In 27 per cent of cases a breach was found but no sanction applied. In slightly more than 50 per cent of these cases, the employee resigned before a sanction was considered. Almost 10 per cent of employees investigated were found to have not breached the Code.

Bullying, harassment and discrimination

Unacceptable behaviours, such as bullying, harassment and discrimination are not tolerated in the APS. As well as being unlawful, these behaviours are associated with low employee engagement, poor wellbeing and high turnover.

Historically, the rate of harassment or bullying reported by APS employee census respondents has remained relatively stable at around 17 per cent. Since 2015, the perceived rate of bullying or harassment in the APS has consistently decreased.

Figure 9: Reported perceived rates of bullying and/or harassment 2012–18

Source: APS employee census

In 2018, 13.7 per cent of respondents perceived bullying and/or harassment in the previous 12 months. Of those, the most frequent type was verbal abuse, followed by interference with work tasks.

The 2018 APS agency survey explored the types of bullying or harassment formally recorded on agency internal reporting systems. Across the APS, 259 formal complaints of verbal abuse were received in 2017–18. This was the most common type of complaint received and is consistent with the high frequency of verbal abuse perceived by respondents to the APS employee census.

The 2018 APS employee census sought information about employee experiences of discrimination. In 2018, the APSC revised discrimination survey questions to better understand the experience of discrimination, including the type experienced in the past 12 months. These changes have affected comparisons across time but will provide a more accurate picture of the current experience of employees with discrimination.

In 2018, 12.3 per cent of respondents to the APS employee census reported discrimination at work in the past year. Most of this discrimination (93 per cent) occurred in their current workplace. Overall, discrimination based on gender (32 per cent) and age (26 per cent) were the main forms identified.

Far fewer complaints of discrimination were recorded in agency reporting systems. Of the 32 complaints recorded during 2017–18, the largest group (13 complaints) was based on race, cultural background or religious belief. This was followed by discrimination based on disability (7 complaints).

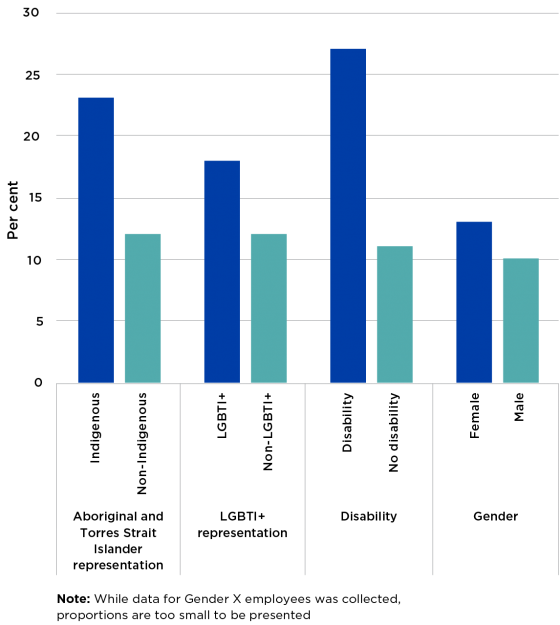

Perception of discrimination, bullying and harassment amongst diversity groups

Marked differences exist in the perceptions of discrimination between respondents who identify as part of a diversity group and those who do not. As shown in Figure 10, respondents who identify as Indigenous21, LGBTI+, or as having a disability, perceived higher rates of discrimination compared to respondents who did not identify as part of a diversity group.

Figure 10: Perceived experiences of discrimination by APS employees of diversity groups

Source: 2018 APS employee census

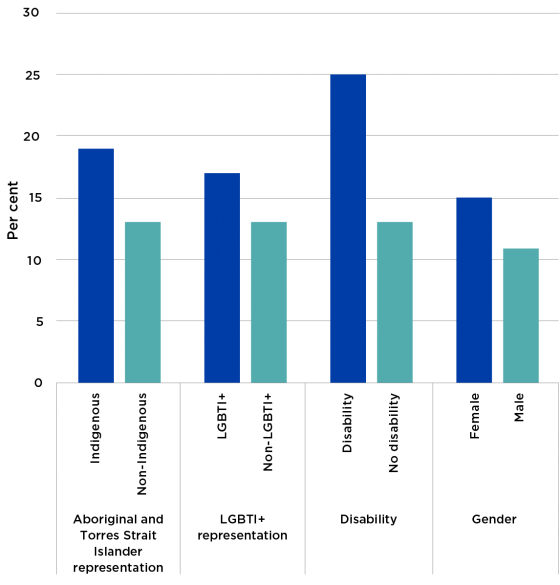

Similarly, there were higher rates of perceived bullying and/or harassment by employees who identified as part of a diversity group.

Figure 11: Perceived experiences of harassment and/or bullying by APS employees of diversity groups

Source: 2018 APS employee census

Successful strategies implemented by agencies to reduce rates of bullying or harassment include:

- providing education and training in various formats such as online, face-to-face, seminars and workshops

- ensuring workplace policies on unacceptable behaviours are regularly updated

- placing information on addressing unacceptable behaviours in easy-to-locate places on agency intranets

- providing workplace support through multiple avenues, such as through workplace harassment contact officer networks, dedicated ‘workplace conduct’ teams, and employee assistance programs.

Corruption

Corruption and perceptions of corruption impact on the trust placed in the APS by the community. All APS employees are required to behave honestly and with integrity in connection with their employment.

In addition to the APS Code of Conduct and APS Values, a robust legislative framework underpins the APS integrity framework. This includes the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2014, the PGPA Act and the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (Cwlth).

Specialist bodies that exist to educate, guide, investigate and prosecute misconduct and corruption across the APS. These include the:

- Australian National Audit Office

- Australian Federal Police

- Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

- Commonwealth Ombudsman

- APSC and Merit Protection Commission

- Inspector-General of Security and Intelligence

- Director of Public Prosecutions.

Each year, Transparency International measures perceptions of corruption across 180 countries, scoring and ranking them based on how corrupt their public sectors are perceived by experts and business executives. The Corruption Perception Index is a measure of all levels of government.

Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index22 shows Australia’s score has steadily declined since 2012 (Figure 12). This indicates an increase over time of citizens’ perception of corruption in the broader public sector. The score of 77 in 2017 places Australia as the 13th least corrupt country. In 2012, Australia ranked 7th. While Australia has seen a marked decline in score and ranking, the average score across the Asia Pacific region is 44.

Figure 12: Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, Australian public sectors, 2012–17

Source: 2017 Corruption Perception Index. Transparency International

Data from the 2018 APS agency survey shows the number of employees investigated under the Code of Conduct for corrupt behaviour. Of the 569 investigated for a suspected breach of the APS Code of Conduct in 2017–18, 78 employees were investigated for behaviour that could be categorised as corrupt. This was a reduction from 121 employees in 2016–17 (Figure 13).

Of the 78 employees, 72 were found to have breached the Code of Conduct. Agencies reported that corrupt behaviours investigated included theft, credit card misuse and submitting fraudulent medical certificates. Corruption cases represent a very small proportion of the already small numbers of employees investigated for breaches of the Code of Conduct.

Figure 13: Number of employees investigated for corrupt behaviour, 2014–18

Source: APS agency survey

Recognising that not all corrupt behaviour may result in an investigation for a suspected breach of the Code of Conduct, the APS employee census asks employees if they have witnessed behaviour that may be serious enough to be viewed as corruption. The definition of corruption in the APS employee census is broad and includes behaviour such as cheating on flex-time sheets and misuse of leave.

In the 2018 APS employee census, 4,395 respondents (4.6 per cent) reported witnessing such behaviour. The most commonly witnessed form of perceived corruption was cronyism, followed by nepotism.

Care needs to be taken when interpreting this data. The data represents employee perceptions and is not evidence of actual corruption. In the interests of collecting accurate data, the APSC has modified its data collection approach several times since data was first collected on perceptions of corruption in 2014.

The approach to data collection remained the same in 2017 and 2018, enabling comparison across these years. The proportion of employees reporting they witnessed behaviours that may be perceived as corruption remained stable (4.5 per cent in 2017; 4.6 per cent in 2018).

More than three-quarters of respondents to the 2018 APS employee census reported that their agency has procedures in place to manage corruption. Almost two-thirds reported it would be hard to get away with corruption in their workplace.

Figure 14: Employee perceptions of workplace corruption risk, 2018

Source: 2018 APS employee census

7 http://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm (accessed 16 October 2018).

8 The Edelman Trust Barometer includes trust in business, NGOs, the media and all levels of government.

9 Edelman Trust, 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, https://www.edelman.com/trust-barometer (accessed 15 October 2018).

10 IPAA national conference: ‘What’s Next?’, 15 November 2017.

11 Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey 2017, https://www.oaic.gov.au/engage-with-us/community-attitudes/australian-c… (accessed 15 October 2018).

12 IPAA Secretary Series: Secretary Valedictory, 7 September 2017.

13 World Justice Project Open Government Index 2015, World Justice Project, (accessed 15 October 2018).

14 Open Government Partnership Australia, Australia National Action Plan 2016–2018, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/australia-national-action-… (accessed 15 October 2018).

15 Australian Government, Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australia’s Second Open Government National Action Plan 2018–2020. http://apo.org.au/system/files/193636/apo-nid193636-1009846.pdf (accessed 15 October 2018).

16 Productivity Commission (2017), Data Availability and Use, Report no. 82, Canberra.

17 Prime Minister and Cabinet, Review of Australian Government Data Activities 2018, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/review_aus_gov_… (accessed 15 October 2018).

18 APSC, Empowering Change: Fostering innovation in the Australian Public Service, 2010,

19 Holmes, B (2011), Citizens’ engagement in policymaking and the design of public services, Research paper no. 1, 2011–12.

20 IPAA, Opening of Innovation Month 2018, 3 July 2018.

21 The terms ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ and ‘Indigenous’ are used interchangeably to refer to Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples.

22 Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2017, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_…;(accessed 15 October 2018)