Chapter 9: Leadership and stewardship

Key points

- Effective leaders shape an ethical and productive culture and build the capability of organisations and teams.

- The Secretaries Board endorsed a set of leadership capabilities for the most senior APS roles, reflecting what is needed now and in the future from senior leaders.

- Most APS employees viewed their SES managers positively, although less so than perceptions of immediate supervisors.

- Immediate supervisors and SES needed to invest more time in developing the capability of employees.

Leadership is central to APS performance. Effective leaders shape an ethical and productive culture and build the capability of organisations and teams. They engage people to give their best in making progress on complex challenges for government, business and the Australian community.

From a system-wide perspective, the leadership of secretaries and agency heads provides vision and direction for the APS. Their leadership provides the impetus to share, collaborate and mobilise efforts across the APS to deliver quality outcomes for government and citizens.

From an organisational perspective, leaders drive performance, helping to steer agencies to more effectively deliver. Leaders engage broadly with ministers and their offices, stakeholders and the community to bring people together to find policy and service delivery solutions.

There is an expectation that leadership is exercised at a range of levels in the APS. It can be seen in the day-to-day use of good judgement, in problem solving and teamwork.

If values are the bedrock of an institution, leadership is what links values with function and purpose. And central to leadership is the capacity to set out a vision.

Peter Varghese, former Secretary, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade70

Secretaries Board72

The Public Service Act was amended in 2013 to formally establish the Secretaries Board. The 2010 report Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for the Reform of Australian Government Administration recommended the establishment of the Board to provide stewardship across the APS.73 The Board is the pre-eminent forum for the debate of key strategic priorities and it develops and implements strategies to improve the APS.

The APS Reform Committee is a subcommittee of the Board. It drives work to ensure the success of the Government’s program to deliver better and more efficient services to citizens and business, including identifying and delivering new short-to-medium term reform opportunities as part of the Roadmap.

The Board is overseeing the implementation of public sector modernisation initiatives under the Government’s $500 million Modernisation Fund investment in the innovation, transformation and sustainability of the public sector.74

After five years of operation the Board is reviewing its operating model and considering changes to strengthen stewardship over the achievement of policy and program outcomes and the effectiveness of people and administrative management. The Board is also actively engaging with the Independent Review of the APS around these issues.

Leadership capabilities for senior roles

We think that management skills, technical competency and subject matter expertise will continue to be critical skills, but they are not enough in themselves. We also need our leaders to be visionary, influential, collaborative, enabling and entrepreneurial. We see those as the crucial additional capabilities for the future. Of course, our leaders need to be self-aware, courageous and resilient.

Finn Pratt AO PSM, Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Energy and Chair of the Secretaries Talent Council, November 201675

As they create leadership pipelines for the future, organisations are grappling with defining requirements for senior leadership roles. They are balancing what is needed for success in the current business environment with the requirements for the future.

Many organisations are explicit when expressing what good leadership looks like for them, linking leadership to their culture and values. Recent research into a range of private sector and public sector organisations indicates some common leadership themes.

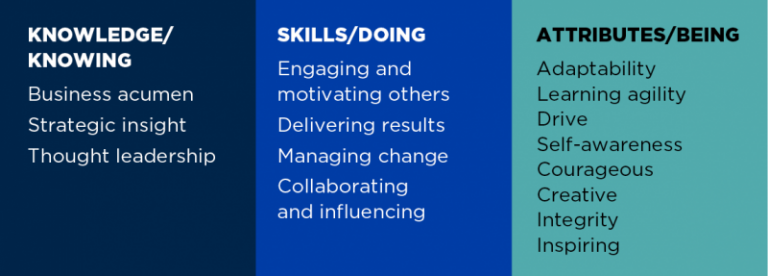

Figure 53: Common leadership themes

Harvard University research76 on leadership for the future emphasises adaptability, self-awareness, boundary spanning, collaboration and network thinking. This research suggests that in an environment characterised by turbulence and complex challenges, more complex thinking skills will be needed, including learning agility, comfort with ambiguity, and strategic thinking.

In 2017, the Secretaries Board endorsed a set of leadership capabilities for the most senior APS roles. These reflect their views on what is needed from senior leaders now and in the future. These capabilities underpin SES talent management and are being used to guide development conversations. They reflect the expectation that in serving government and citizens, senior APS leaders will provide vision and direction, be influential and collaborative, look for new ways of doing things that add public value, and build the capability of their teams and organisations.

Leadership capabilities for senior roles

Visionary

To provide the best policy advice to government, senior leaders need to be able to scan the horizon for emerging trends, identifying opportunities and challenges for the nation.

Influential

To take the government’s policy agenda forward, senior leaders need the capacity to persuade others towards an outcome, winning and maintaining the confidence of government and key stakeholders.

Collaborative

In making progress on issues that cut across agencies, sectors and nations, senior leaders need to be able to develop relationships, build trust and find common ground with others. An openness to diverse perspectives is critical.

Entrepreneurial

In finding new and better ways of achieving outcomes on behalf of government and citizens, senior leaders need to be able to challenge current perspectives, generate new ideas and experiment with different approaches. They also need to be adept at managing risk.

Enabling

Creating an environment that empowers individuals and teams to deliver their best for government and citizens is a core requirement for senior leaders. This includes setting expectations, nurturing talent and building capability.

Delivers

Senior leaders need to be highly skilled at managing the delivery of complex projects, programs and services. This includes harnessing the opportunity provided by digital technology to improve delivery outcomes for citizens.

Self-awareness, courage and resilience

These personal qualities sit at the heart of effective leadership in the APS. For APS leaders, mobilising and driving change requires a strong capacity for action and agency on the one hand, and an equally strong capacity for understanding and contending with constraints. Self-awareness, courage and resilience enable senior leaders to hold steady through the challenges of leadership.

Leadership performance

Secretaries

The Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Australian Public Service Commissioner conduct annual performance discussions with secretaries. This practice started in 2013. This year the methodology changed to include an assessment process against the new leadership capabilities, drawing on feedback from ministers, stakeholders, peers and direct reports, as well as interviews with an organisational psychologist.

The assessment went to three dimensions of a Secretary’s role: chief advisor to the Minister; leader of a department; and steward of the APS. This process allowed for a deeper discussion with secretaries aimed at providing a basis for enhancing the individual and collective performance of the most senior leadership group.

APS leaders have been successful in establishing a responsive and action-oriented culture. The challenge remains to balance this against the requirement to be stewards of the APS and bring a holistic approach to complex and interconnected issues.

SES and immediate supervisors

Every year the APS employee census measures employee views about the quality and capability of leaders at all levels.

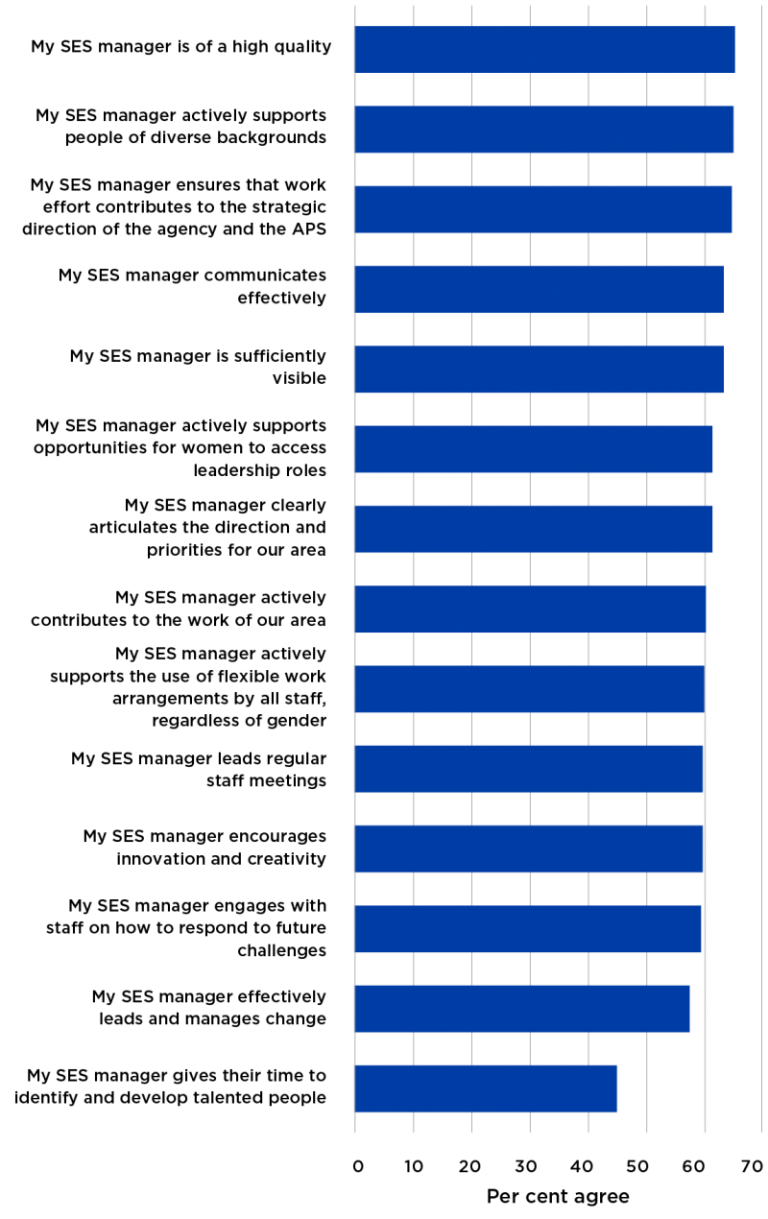

Most APS employees view their SES managers positively, although less so than their immediate supervisors (Figure 54). APS employees were most likely to agree that their SES manager was of high quality at 65 per cent, an increase from 62 per cent in 2017. This is closely followed by supporting people of diversity and ensuring work effort contributes to strategic direction. The lowest result was in response to whether SES gave time to identify and develop talented people, at 45 per cent. This lower score is a small increase on last year at 43 per cent.

A smaller proportion of employees (58 per cent) also perceived their SES managers to be able to effectively lead and manage change. The ability to manage change well is key to implementing APS reform, steering new policy and service delivery. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, Managing change.

Differences in the perceptions of SES managers exist, depending on their physical location to the respondent. Perceptions of an immediate SES manager are more positive when this manager is in the same office as the respondent, even if their work location is on a different floor. When an SES manager is in a different office, regardless of whether the office is in a different town or city, perceptions of the immediate SES manager are lower.

Figure 54: APS employee perceptions of their immediate SES managers

Source: 2018 APS employee census

Across both immediate supervisor and SES manager questions, employees were less likely to agree on questions relating to developing employees, and on identifying and taking time to develop talent. Again, these relate to the ‘enabling’ capability. The low responses are consistent with previous years. Lower scores on these questions suggest that immediate supervisors and SES may not be investing time in capability development of employees. It may also suggest a lack of skill in coaching and performance management. This is of significant concern as the APS grapples with the need to rapidly build capability. Leaders are a key source of development and there may be a need to significantly lift their performance in this area.

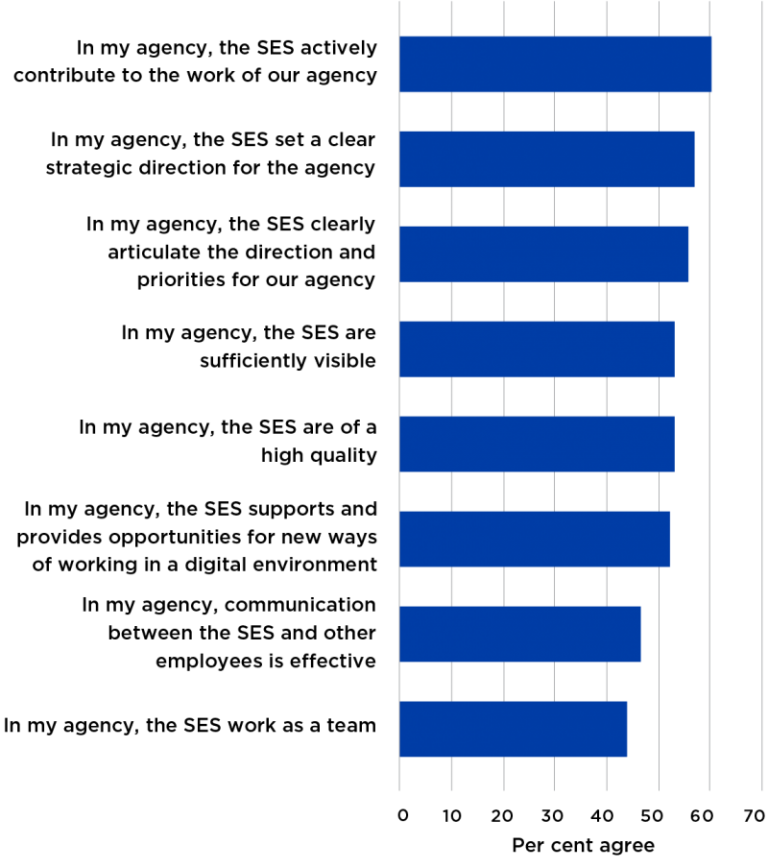

The APS employee census also captures employee perceptions of the SES as a cohort within their agency. Figure 55 reports on the general impressions of this group.

Figure 55: APS employee perceptions of the SES managers within their agency

Source: 2018 APS employee census

Consistent with past years, employee perceptions of the SES group in their agency are lower than perceptions of their immediate SES and supervisor. The highest rated perceptions of the SES group include contributing to the work of their agency, setting strategic direction and articulating priorities. These align with the ‘delivers’ and ‘visionary’ capabilities.

However, employees are less likely to agree that their SES work as a team, with only 43 per cent of respondents agreeing to this question. This may point to a weakness in the ‘collaboration’ capability.

This is a concern given the cross-cutting nature of the issues senior leaders need to progress on behalf of government and citizens. Working across teams, agencies and sectors is a core requirement in a senior role and there appears to be a need to improve capability in this area.

At the individual manager level, as in previous years, the 2018 APS employee census reveals that most APS employees view their immediate supervisor favourably (Figure 56). Responses to all questions relating to immediate supervisor were very positive, ranging from 72 per cent to 88 per cent. Employees rated their immediate supervisor highly, regardless of their supervisor’s normal work location (for example, same office, different town or city).

Figure 56: APS employee perceptions of their immediate supervisors

Source: 2018 APS employee census

APS employees were most likely to agree that their immediate supervisor treats people with respect, supports people from diverse backgrounds and holds employees to account. Though still a reasonably high result, employees were least likely to agree that their supervisor helped develop their capability. This has remained consistent across time and aligns with the trends for SES leaders.

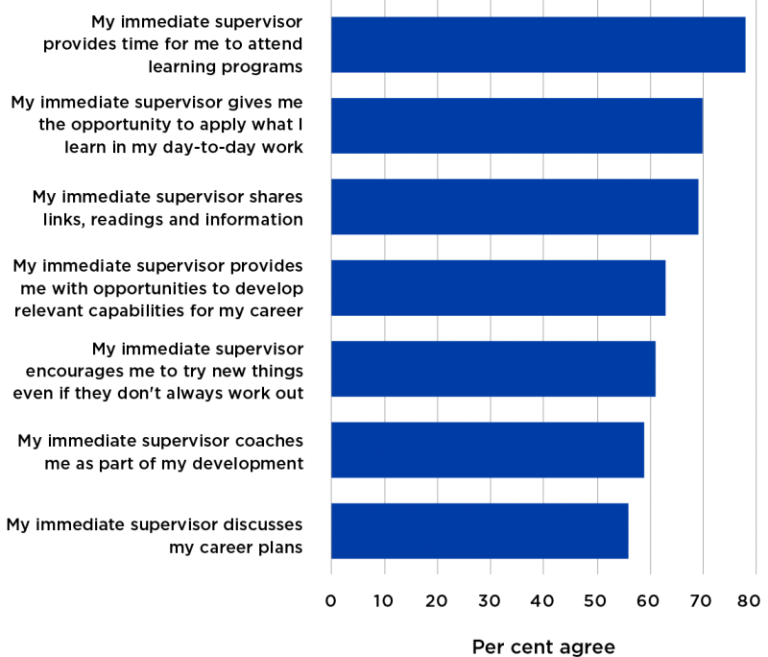

An analysis of the approaches immediate supervisors took to develop employee capability reveals an interesting pattern (Figure 57).

Figure 57: APS employee perceptions of their immediate supervisors’ approach to developing capability

Source: 2018 APS employee census

Immediate supervisors were most likely to provide time for their employees to attend learning programs and provide opportunities for employees to apply what has been learned. Sharing links to useful information is also a common approach. The least commonly used approaches to developing capability are for supervisors to discuss individual career plans and provide coaching as part of development.

Arguably, coaching should be the most likely approach given the day-to-day working relationship between a supervisor and an employee. Delivering work outputs provides many opportunities for guidance and coaching.

The lower likelihood of career conversations aligns with emerging themes from recent SES talent-management processes, where few SES appear to have had career conversations. In the 2018 APS employee census, SES respondents, trainees, apprentices and graduates were the most likely to have had career plan discussions, although still relatively low at 66 per cent. APS and EL employees were less likely to have had a career plan discussion, both at 56 per cent.

72 IPAA Secretary Series: Secretary Valedictory, 9 June 2016.

73 Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration (2010), Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for the Reform of Australian Government Administration, Canberra.

74 2017–18 Budget, Paper 4.

75 IPAA ACT Conference: ‘Identifying and Developing Future Leaders’, 10 November 2016.

76 Petrie, N (2014), Future Trends in Leadership Development. Center for Creative Leadership White Paper. Included a review of approaches to developing leaders across the schools of Harvard University (education, business, law, government, psychology); a literature review; interviews with 30 experts in the field.