Building on the data—Gender equality in the APS

The following information draws together data and consultation insights, which inform the actions outlined in the Strategy.

Gender representation

In 1968, 2 years after the removal of the Marriage Bar (which forced women to leave the APS when married), men dominated the APS, and just one in 4 employees were women. Today nearly 3 in 5 employees are women. Proportionately there are now more women in the APS (60.2%) compared to the Australian labour market (47%). The APS has become an employer of choice for women, where women account for almost 3 in every 5 new ongoing recruits.

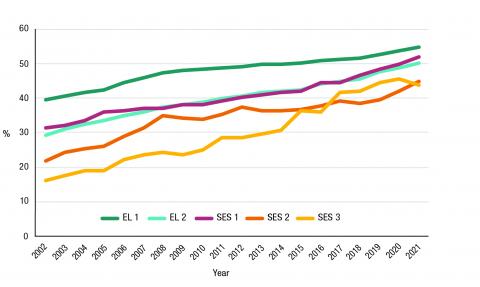

Women are well represented at all classification levels in the APS including the Senior Executive Service (SES). Women now comprise 50% of the total SES cohort for the first time. For the past 6 years, the proportion of promotions into and within the SES for women has exceeded 50% on average (Figure 1). In 2020-21, almost 60% of promotions at SES 1 (62.7%) and SES 2 (56.6%) and only 26.7% at SES 3 were women.

While we must continue to embed the gains made by women in the APS, this Strategy is not only about women. A range of actions are required to benefit representation of all gender identities and the importance of promoting gender inclusivity.

Figure 1. Proportion of women in leadership roles (30 June 2021).

COVID-19 has amplified the fact that capacity to work flexibly is critical to business continuity, health and wellbeing, workforce planning and risk management. The pandemic has also reinforced some very human aspects of flexible work, including the importance of connection, caring, collaboration and getting to know our colleagues.

Flexible work and part-time

Flexible working is about rethinking the where, when and how work can be done, in a way that maintains or improves business outcomes. It can improve employee engagement and commitment in the workforce; increase productivity; help attract and retain talent across diverse workforce demographics; foster a sense of reciprocity among employees, which can improve customer service; and can enable new business models with broader benefits to customers and society more generally.12

There is a strong gender equality rationale for providing flexible ways of working for all employees. Encouraging men’s uptake of flexible work, for example, enables sharing of caring responsibilities. Research suggests that men who work flexibly are more productive in their jobs, experience less stress and burnout and have a higher sense of purpose and wellbeing.13 Not relying on women to manage all of the caring responsibilities can enable women to increase their hours, ultimately helping to increase women’s workforce participation, close the superannuation gap and potentially increase promotion opportunities.

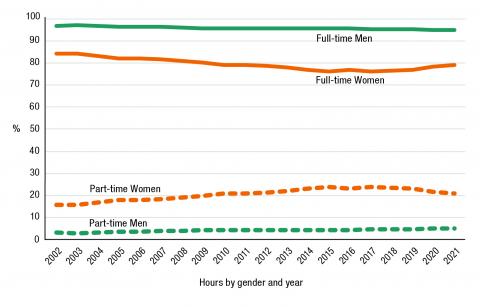

Over the past 20 years, while part-time work (one aspect of flexible work) for women has increased steadily, for men it has remained largely unchanged (Figure 2). Our consultations indicated a range of reasons why men are less likely to work part-time, including judgement from others about their commitment to their work and career, as well as the reduced salary as a result of part-time work.

Figure 2. Hours by gender and year (30 June 2021).

COVID-19 has amplified the fact that capacity to work flexibly is critical to business continuity, health and wellbeing, workforce planning and risk management. The pandemic has also reinforced some very human aspects of flexible work, including the importance of connection, caring, collaboration and getting to know our colleagues.

Breastfeeding Friendly Workplaces

Only a small number of APS agencies are accredited Breastfeeding Friendly Workplaces. This is despite the launch of the Australian Breastfeeding Strategy: 2019 and Beyond,14 endorsed by the Health Council, which includes a priority action for governments at all levels to take steps towards becoming ‘breastfeeding friendly’. This statistic accords with what we heard from employees during consultations that there remains inconsistent support from workplaces for breastfeeding on return to work, with some employees reporting a lack of appropriate facilities to express milk during lactation breaks, or simply the privacy to feed their child whether it be through breastfeeding, or by bottle.

A related theme was about support for employees while on an extended period of leave. We heard that managers lack information about their role in supporting employees during this time, including to assist employees transition back to work.

Harassment and bullying

While there has been some increase in formal complaints in relation to workplace harassment and bullying over the last 3 years, the numbers remain small relative to the size of the APS workforce. However, our consultations indicated that APS employees across agencies experience everyday sexism and more insidious forms of harassment and bullying, which often go unreported.

Employees told us of unacceptable workplace behaviour from colleagues that related to a range of gendered issues including sexual harassment, caring responsibilities, judgements about career aspirations and breastfeeding, to name a few. While there are a number of reasons why employees did not report such incidents, recurring concerns involved not being taken seriously or believed, as well as limited confidence in a satisfactory resolution.

We heard through our consultations about the need to provide opportunities for employees to share their experiences in a safe environment and empower others to call out inappropriate behaviour. Employees noted that creating a trusted environment may assist in calling out and reporting harassment and bullying.

Agencies and the APSC also strongly support the implementation of recommendations from the Australian Human Rights Commission Respect@Work report, and the subsequent Government Roadmap for Respect to preventing and addressing sexual harassment, and support meaningful cultural change in Australian workplaces.15

APS occupations

The demographics of the APS workforce (including hiring and promotion) largely reflect the Australian labour market and the gender mix of graduates from tertiary and vocational institutions. The gender balance data suggests that the APS is a leader in some of these occupations.

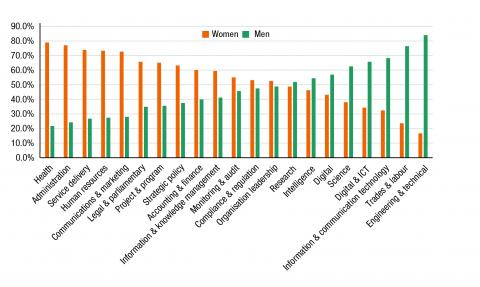

Gender-balanced workplaces benefit employees, families, organisations and the economy.16 Yet in the APS there are many job types that are either dominated by women or dominated by men (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gender breakdown by type of work performed.

In our consultations, male APS employees spoke about facing barriers related to working in female-dominated roles, for example executive and corporate support roles. They noted feelings of exclusion and being discouraged from highlighting these important skills and experiences on their Curriculum Vitae. In regards to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) related roles, women in particular face barriers at all levels of the pipeline including during their education and at all levels in the workforce, particularly presenting at senior levels.17

To build greater gender balance in job types both in the APS and beyond, there is already work underway:

- actions at a whole of community level—for example, as part of the Women in STEM Decadal Plan and the Women’s Economic Security Statement 2020

- actions at a whole of APS level—for example, as part of the Delivering for Tomorrow: APS Workforce Strategy 2025 and the Professional Streams. These seek to address imbalances through a skills and capability lens18

- actions at an agency level— for example, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is targeting a 40/40/20 gender balance in female dominated Executive Assistant roles.

The SES are also spread similarly across occupations with many occupations dominated by one gender, although this gap is smaller.

The proportion of other gender identities by type of work performed in the APS ranges from 0% to 1% across all occupations. This further demonstrates the need for better analysis of gender data and reporting systems.

Gender pay gap

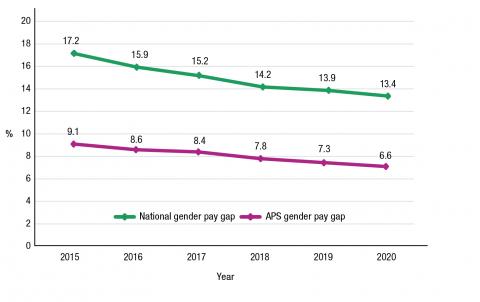

The gender pay gap is the difference between male and female employees’ average weekly full-time equivalent earnings, expressed as a percentage of male earnings. Based on 2020 APS average base salaries for men ($99,082) and women ($92,536), the gap in the APS is less than half of the national gender pay gap of 13.4% for the same period

(Figure 4). It is slightly higher than the gender pay gap for the Public Administration and Safety industry category (7.3%) which is the sector with the lowest gap.19

The gender pay gap reflects differences in representation of males and females at each classification level. More specifically, this involves overrepresentation of females at lower classification levels (APS 2–6).20 In the APS, women are considered to be at pay parity for most classification levels with the differences in these classifications in the range of +/- 1%. Graduate, APS 2, SES 2 and SES 3 classifications have slightly larger pay differences.21 The representation of male and female employees at the highest classification levels is moving towards parity and this is reflected in a reduced gender pay gap across the APS.

Figure 4. Average gender pay gap trends with data table, 2015–20.

Superannuation

On average, male public sector superannuation balances are 19.8% higher than females across all age groups. Since 2015, male median pension amounts have been consistently between 40% and 50% higher than female annual pensions. However, females are not retiring any earlier than males.22

The Retirement Income Review 23 noted that the retirement income gap for women ‘is the accumulated result of economic disadvantage faced by women in their working life—lower wages than men, more career breaks for child-rearing and caring for others, and more part-time work.’

This is compounded by the findings of the 2019 Community and Public Sector Union What Women Want Survey 24, which found that:

- a third of women did not know what type of superannuation scheme they belonged to

- 1 in 10 women do not know how much money they have in their superannuation account

- over half of women had never been to any superannuation information/training sessions.

- The survey noted the need for all employees to have a basic level of superannuation knowledge early on in their career.

The survey noted the need for all employees to have a basic level of superannuation knowledge early on in their career.

NOTE: All actions have been specifically designed to improve equality for all gender identities as an outcome. We will continue to seek opportunities to broaden the data analytics to give insights into the issues, and where there is opportunity to broaden our actions.