Strategic context and objectives

This is an independent report representing the views of the Hierarchy and Classification Review panel.

The APS is a complex and diverse enterprise

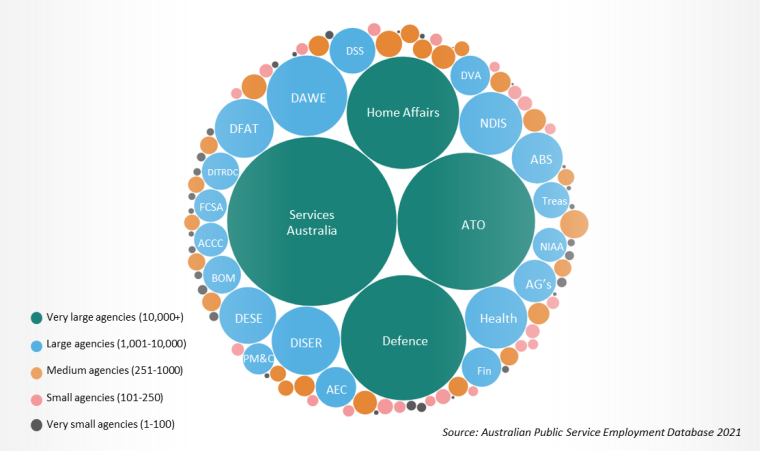

The APS of 2021 is complex and heterogeneous, with over 150,000 employees working in more than 100 agencies that vary in size (Figure 1).

Figure 1 | APS agencies by size[1]

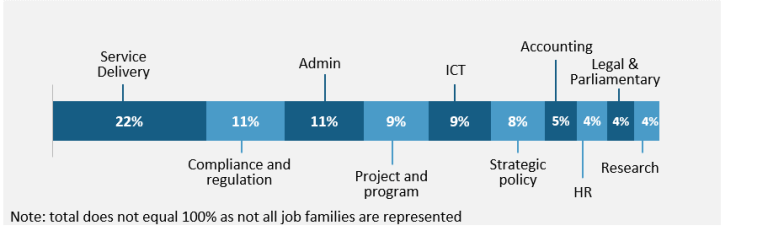

The APS serves the government and Australian citizens in a variety of functions, including service delivery, regulation and compliance, policy and enabling roles (Figure 2).

Figure 2 | APS workforce by job family[2]

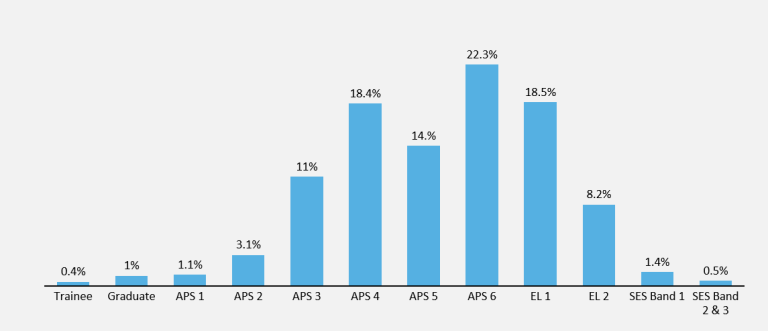

The composition of the APS workforce is changing, with APS6 the most common classification levels in 2021 (Figure 3). Comparatively, APS4 was the most common level in 2002.[3]

Figure 3 | Proportion of APS employees by classification[4]

The APS is too hierarchical and needs a flatter structure to better serve the government and Australian citizens

In December 2019, the Government committed to an ambitious APS Reform Agenda in response to the Independent Review of the Australian Public Service (‘Independent Review’). The Independent Review suggested the APS typically operates in ‘silos, rigid hierarchies and traditional ways of working’ and called for it to ‘become a much more dynamic and responsive organisation’.[5] It made a number of recommendations to support a united, citizen-centric and adaptive APS, including undertaking this Hierarchy and Classification Review. This review is a significant next step looking at how to configure a modern, flexible APS to respond quickly, empower staff and deliver for the government and citizens into the future.

It is now three years since this discussion commenced and our consultations confirmed the Independent Review’s conclusion that the current classification system has too many layers, reflects outdated working practices and needs modernising. The Panel heard the APS workforce lacks confidence in the current classification structure and wants to see an updated system that empowers staff at all levels, adopts flatter structures and recognises expertise and contribution, not rank.

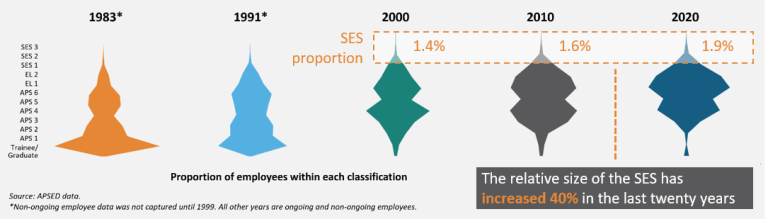

The current classification structure and its rigid hierarchy serves as a basis for reporting tiers, contributing to an excessively layered approach to decision-making. This has consequences for both enterprise efficiency and delivery of services. Figure 4 shows the shifting profile of the APS since the 1980s.

Figure 4 | The shape of the APS over time

Notably, the relative size of the Senior Executive Service (SES) has increased by 40% over the past 20 years as the APS has become progressively top heavy. Consultations cited the demands of Ministers for enhanced risk management at senior levels as the reason for this growth. This profile also prompts reconsideration of where the ‘natural’ breaks are in APS classifications.

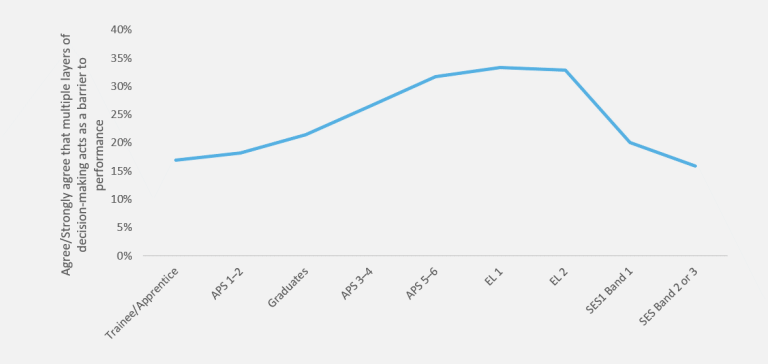

A strong theme throughout engagement with APS employees was that classification levels are used as a determinant of who to listen to, who to consult and who to value. A reluctance to delegate and deference to reporting lines, means the right people are not always involved in decision-making, a diversity of perspective is missed and employees are left feeling undervalued and untrusted. We heard in consultations that the APS competes with the private sector for talent, and consistently sees leakage of staff at junior levels because the system’s rigidity prevents the full utilisation of their capability. Figure 5 shows how different APS cohorts view layers of decision-making.

Figure 5 | Perception that layers of decision-making are a barrier to performance, by level[6]

The APS classification structure needs modernising to adapt to changing workforce trends and ongoing disruption

While the current classification framework heralded ground-breaking reforms in the mid-1980s, it has undergone minimal reform since. This led the Panel to consider whether it is fit for purpose for the next 10‑20 years.

Past reviews of the classification framework

The 2011 Beale Review of the Senior Executive Service (SES) recommended a minor revision to the Public Service Classification Rules 2000 (‘Classification Rules’) to abolish the Senior Executive Service (Specialist) classification and recommended mandatory assessment of SES positions against APS-wide SES work level standards.[7] That review was motivated by the desire to manage growth in SES levels, rather than consideration of broader APS organisational design or culture.

The complementary 2012 review of APS classifications, led by the APSC, recommended the gradual removal of ‘legacy’ classifications, many of which denote specialist roles used by a small handful of APS employees (e.g. Antarctic Medical Practitioner Level 1) or which refer to now obsolete entities (e.g. DAFF Bands 1-3; Customs Levels 1-5) and which remain in the Classification Rules. Both of these reviews took a narrower view of the purpose of the classification framework than this review.

|

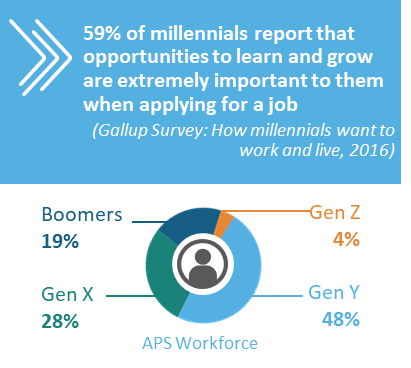

Work in the APS will continue to change over the next 25 years, thus the profile of skills needed to deliver for government and Australians will also shift. APS functions have already adapted to increased automation and more digital ways of working. Heightened community expectations of the public sector’s responsiveness, service and agility, as well as a turbulent external environment, feed a more complex work environment. As the work becomes more complex, there is an increased requirement for the APS enterprise to work flexibly and for staff to adapt to new roles and work expectations. At the same time, expectations of workers are evolving, wanting to join purpose-driven organisations with clarity about how they contribute to achieving the organisation’s objectives. The APS is increasingly seeking to attract and retain employees who value flexibility, investment in their capability and opportunities to work in more agile environments. Today, 50% of employees in the APS are ‘digital natives’ from Gen Y and Gen Z,[8] who expect the nature of their roles to encompass advances in technology and more hybrid working models.[9] The APS is sourcing talent from an increasingly competitive labour market, where it will need to demonstrate a focus on strategic people management, culture, development and workforce strategy to attract the right skills and expertise into the APS.[10] |

|

The future of work and the Intergenerational Report

The 2021 Intergenerational Report noted the radical changes in the occupational structure of the Australian labour force in the last 50 years, including the decrease in manual roles and the increase of professional, community and personal service workers. The report notes the main drivers of these shifts include “increasing global interconnectedness, technological change and automation”.[11]

In understanding what the future of work holds for Australia, the Intergenerational Report noted that “new technologies will mean jobs are redesigned to take maximum advantage of the capabilities enabled by new technologies” and emphasised the need for “[b]usinesses…to invest in improving managerial expertise to best manage how these enhancements are integrated into organisational work practices”.[12]

We strongly agree this learning should be applied in the APS context, together with the Intergenerational Report’s support for ‘lifelong learning’ to achieve a resilient and adaptable workforce that can support future economic growth.

Structural transformation will create a more agile and future-fit APS

The rigidity reinforced by the current APS classification structure stands in striking contrast to the flatter, team‑based and matrixed structures of many organisations consulted through this review. Leading organisations embrace a mindset of constant adaptation to ensure their workforce is able to respond in a rapidly changing world to meet the needs of customers/citizens.[13]

Many public and private sector organisations are moving to flatter, more dynamic structures with greater spans of control to enable a system that is more flexible to respond and reconfigure quickly to changing government priorities and citizen expectations. Reforms in the UK Civil Service, for example, highlight the need for the workforce to be as mobile and agile as possible, to manage crises and disruption as they become the new normal.[14] This approach is also consistent with the 2014 APS Framework for Optimal Management Structures, which notes that “[m]anagement structures with fewer organisational layers and broader spans of control improve productivity and support change.”[15]

The APS has shown an impressive ability to respond quickly and effectively to emergencies, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic. In these situations, teams coalesce quickly and use flatter structures, and work is assigned to those with the relevant knowledge, skills and experience (with less attention to classification or organisational affiliation). They collaborate efficiently to achieve desired outcomes, prioritise appropriately, making decisions quickly while still producing robust and comprehensive advice. The challenge is to introduce the flexibility the APS embraces when confronted with crises in its day-to-day operations.

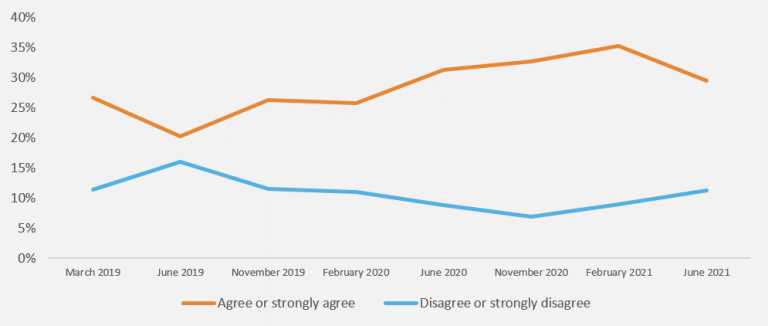

APS employees consulted for the review referred positively to this experience. The 2020 APS Census data showed that 89% of respondents agreed their working group successfully adapted to new ways of working and 80% of respondents agreed their agency quickly adapted and responded to changing priorities in response to COVID-19. The positive impacts were evident to the APS’s customers as well. In the 2021 Citizen Experience Survey, perceptions of APS responsiveness increased markedly (Figure 6). However, APS employees expressed concern that any benefits gained from COVID-19 responses may be short lived, with a reversion to less flexible, less efficient and more hierarchical practices already happening.

Figure 6 | Public perceptions of service responsiveness: "Australian Public Services are Responsive"[16]

There is a genuine opportunity for the APS to harness these experiences and build the structures that will support a contemporary, engaged and flexible workforce.

The APS Optimal Management Structure (OMS) Framework

The APS already has sensible, although rarely utilised, guidance on organisational design, known as the 2014 APS Framework for Optimal Management Structures (‘the Framework’). The Framework was developed in response to the 2014 National Commission of Audit finding that ‘there [was] significant scope to improve structures within many Commonwealth organisations.’[17]

The Commission did not advocate specific span of control targets, arguing Departmental Secretaries ‘should be responsible and accountable for their own management practices and structures.’[18]

The Framework has five key principles that underpin the design of an agency’s management structure:

- Vertical design: An agency should not have more organisational layers than is absolutely necessary to perform effectively.

- Accountability and decision-making: Decisions should be made at the lowest practical level.

- Relative complexity of tasks: The optimal number of direct reports will depend upon the type of work being managed.

- Innovation and adaptability: Structures should maximise the opportunity for innovation and provide flexibility to respond to change.

- True work value: Jobs should be classified across the APS according to work value.

The Framework indicates the optimal number of organisational layers should be, in most cases, between 5-7. The Framework also notes classification levels do not determine layers and a layer may include several levels. The Framework also provides a guide for the number of direct reports for different APS work types, varying between 3-7 for specialist policy and 8-15+ for high volume service delivery.[19]

While we agree the Framework provides a sensible basis for APS organisational design, we would like to see a push towards a span of control of generally 8‑10 direct reports (discussed in Recommendation 5).

Unfortunately, there is little evidence that the APS has taken action to implement the Framework. This is despite a Secretaries Board agreement for all agencies to conduct a self-assessment of their existing management structures against the Framework’s principles and benchmarks; and develop a plan to achieve improved management structures over a three year period from 2015 to 2018.

This experience has influenced our view that it is appropriate to recommend a firm change to the Classification Rules, rather than a softer, policy-based approach.

Investment in culture, leadership and capability at the enterprise level is critical for a well-equipped ‘One APS’

The strong message from our engagement across all sectors was the need to take a holistic approach to structural change, attending to purpose, leadership, capability, culture and working practices to meet the changing needs of government and Australians. Over the last decade, several State Governments have undertaken structural change which has supported demonstrable cultural change and better delivery of services for citizens. Structural reforms in NSW, for example, have seen a more efficient, responsive and citizen-centric public service emerge (Appendix E | Comparison with Australian State and Territory public services refers), as well as the NSW public service becoming an employer of choice.[20]

APS employees require new skills to work in a changed environment with a different approach to decision-making, accountability and risk management. This is particularly true for the pivotal middle manager cohort who most acutely feel the impact of overly layered approaches to decision-making. Investment in leadership and people management capability will enhance the APS’s ability to deliver effectively.

The Panel also heard from many private sector Australian-based companies with international operations about how they place immense value on people management. The APS is noticeably less mature in the management of whole-of-enterprise people matters and should embrace strategic people management as a key way of building capability to better deliver government objectives and retain a skilled workforce.

Acting now will ensure sustained delivery into the future

The APS has shown it can implement better practices and behaviours that produce better outcomes as well as provide more rewarding careers for the employees who are the APS’s lifeblood. The APS should act swiftly to capture and build on this momentum.

Engagement with officials in other State/Territory and international governments reinforced the common imperative for public services globally to build adaptation into the way they think about their organisations. There is a genuine opportunity for the APS to harness these experiences and build the structures that will support a contemporary, engaged, flexible and agile workforce that will be positioned to deal with 21st century issues as they arise.

This package of recommendations complements ongoing current APS reforms. To ensure success, APS leaders must take a complete view so that changes introduced are presented as a mutually reinforcing whole and implemented consistently as a single enterprise, to reinforce ‘One APS’. With such focus and commitment, the APS can confidently position itself as a contemporary enterprise, where all arms of government can work in an increasingly integrated manner to ensure they are fit for the challenges to come over the next several decades.

[1] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) APS Employment database (APSED), APSC website.

[2] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) APS Delivering for tomorrow: APS Workforce Strategy 2025.

[3] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) APS Employment database (APSED), APSC website.

[4] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) State of the Service Report 2020-21, APSC website.

[5] Commonwealth of Australia (2019) Our Public Service, Our Future. Independent Review of the Australian Public Service.

[6] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) APS Employee Census 2021 [unpublished data set].

[7] Commonwealth of Australia (2011) Review of the Senior Executive Service.

[8] Australian Public Service Commission (2021) APS Employment database (APSED), APSC website.

[9] Gallup Report (2016) How Millennials Want to Work and Live, Gallup.

[10] Williamson, S et al. (2021) Future of Work Literature Review: Emerging Trends and Issues, UNSW.

[11] Commonwealth of Australia (2021) 2021 Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

[12] Commonwealth of Australia (2021) 2021 Intergenerational Report: Australia over the next 40 years.

[13] Kleinman, S, Simon, P & Weerda, K (2020) Fitter, flatter, faster: How unstructuring your organization can unlock massive value, McKinsey and Company.

[14] Government of the United Kingdom (2021) Declaration of Government Reform.

[15] Australian Public Service Commission (2014) The APS Framework for Optimal Management Structures, APSC website.

[16] Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2021) Citizen Experience Survey, PM&C website.

[17] Commonwealth of Australia (2014) Towards Responsible Government ‐ Report of the National Commission of Audit: Phase Two.

[18] Commonwealth of Australia (2014) Towards Responsible Government ‐ Report of the National Commission of Audit: Phase Two.

[19] Australian Public Service Commission (2014) The APS Framework for Optimal Management Structures.

[20] NSW Government (2021) NSW Government named employer of choice among Australia's graduates [media release], NSW Government, 12 February 2021.